Abstract :

– For several years now, the investment rate has been declining in France, even though investment spending was one of the drivers of growth before the crisis.

– Certain imbalances caused by the French economy’s entry into the eurozone and the onset of the crisis are behind this slowdown.

– The economic policies implemented in France (CICE tax credit, reduction in employer contributions) and in Europe (quantitative easing by the ECB, Juncker plan) should encourage a recovery in investment in France in 2015.

– However, certain factors are likely to limit the extent of this rebound: weak demand and low capacity utilization rates, and the financial situation of governments and businesses.

Economic growth has been sluggish in France for several years. Pressure from the European Commission to consolidate public finances and an increase in French household savings have led to a slowdown in consumption. In addition, the loss of momentum in intra-eurozone trade is weighing on external demand. Finally, investment has been falling for several quarters after rebounding in 2010-2011. We will focus on this last point in order to understand why gross fixed capital formation is experiencing such difficulties today, after having been one of the pillars of growth in France for many years.

1. Investment, a pillar of French economic growth

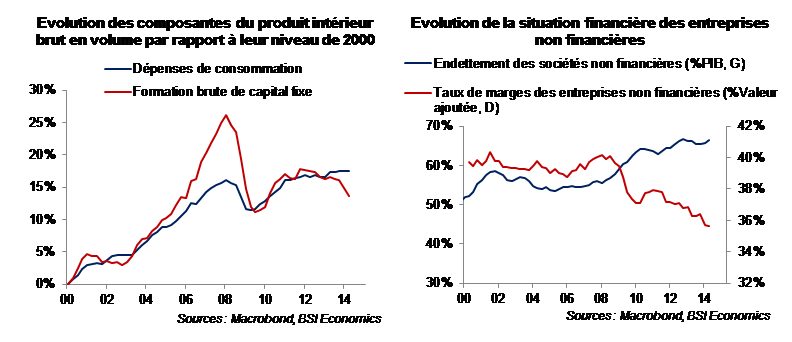

Driven in particular by strong domestic demand, France experienced relatively dynamic growth in the years following its entry into the euro zone (around 2.2% on average over the period 2000-2007) before slowing significantly since the onset of the crisis (0.2% on average over the period 2008-2014). Over the last fifteen years, growth in French gross domestic product has been largely driven by demand for capital goods. The French economy’s investment rate, which measures the weight of investment in GDP, is one of the highest in Europe, at 22% in 2014 (compared to 19% in the United States, 18% in Germany, Spain, and the Netherlands, 17% in Italy, and 15% in the United Kingdom), according to IMF estimates.

During the early 2000s, gross fixed capital formation by businesses grew faster than consumption in France, peaking in 2007. The volume of investment fell sharply during the 2008-2009 recession, before rebounding in 2010-2011, albeit insufficiently to return to its pre-crisis level. Since this rebound, investment has experienced a new downturn, which began in 2012, contributing to the slowdown in the French economy, which has been weakly driven by public consumption in recent years.

The gloomy economic climate and lack of demand are not the only reasons for this decline in investment in France, which can also be explained by the financial difficulties experienced by French companies. Indeed, if we look at the evolution of French gross domestic product by income, we can see that for several years there has been a break with the long-term trends in the distribution of added value between wages and gross operating surpluses (profits), to the detriment of companies. This phenomenon has resulted in a decline in the profit margins (the ratio between companies’ gross operating surpluses and the value added they create) of non-financial companies.

2. A two-stage shock to business investment

Despite the steady performance of investment volume in France since it joined the eurozone, the decline in investment in France in 2014 reflects weaknesses in certain sectors that predate the onset of the crisis.

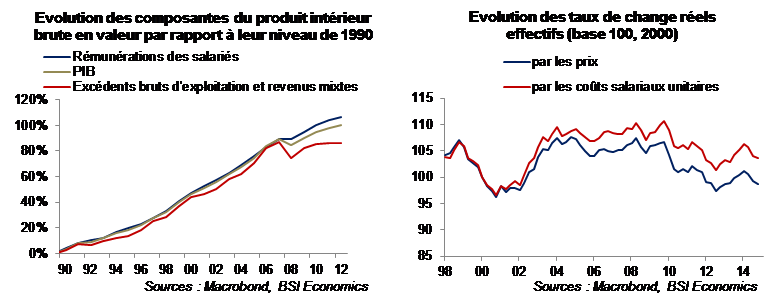

Since joining the eurozone, France has seen its global and European export market share decline for several reasons. Its cost competitiveness deteriorated significantly in the early 2000s, resulting in an increase in its real effective exchange rate. This lack of competitiveness was exacerbated by international price competition and a reduction in the profitability of French companies in exposed sectors. By lowering their prices, they suffered a deterioration in their margins and their self-financing capacity. Financially weakened, French exporting companies reduced their R&D spending, which could have promoted a move upmarket and generated non-cost competitiveness gains, and suffered an acceleration in the decline of industrial activity in terms of value added. At the same time, the wage deflation policy pursued by Germany, France’s largest trading partner, amplified France’s difficulties by reducing domestic demand and therefore imports. Under these conditions, gross fixed capital formation declined in most exposed sectors in France, particularly manufacturing.

Combined with France’s existing competitiveness problems, the crisis has dealt a further blow to profitability, causing a sharp rise in the number of companies in exposed sectors, already in financial difficulty, going bankrupt. The further critical weakening of corporate profit margins in a deteriorating economic environment is now partly due to the resistance of payroll growth despite the slowdown in activity.

In the service sectors, investment has held up relatively well since 2007, after growing rapidly in previous years, and in 2014 was more than 30% above its 2000 level. This is not the case in industry. In the construction sector, investment has fallen sharply since 2007, after experiencing strong growth in the early 2000s. In the manufacturing sectors, the increase in investment volume was weaker than in other sectors in the years leading up to the crisis, and its decline since 2007 has brought it back to its 2000 level.

The decline in private investment spending in France was partially offset by an increase in public investment in 2008-2009. However, investment slowed in 2010 as private investment recovered and the eurozone pursued a strategy of reducing public deficits. The renewed decline in private investment that began in 2012 was initially accompanied by a further increase in public investment. Since early 2014, public and private investment volumes have been falling together for the first time since 2008, leading to this worrying decline in the level of gross fixed capital formation in France.

3. Changes in investment demand

The share of wages in gross domestic product has thus increased, to the detriment of companies’ gross operating surpluses. This phenomenon has enabled the French economy to be particularly resistant to the episodes of recession that have affected the eurozone economy, thanks to strong consumption, which has sustained domestic demand. At a time of (timid) recovery, this macroeconomic drain on businesses severely limits their ability to invest. As a result, sectors producing investment goods, which depend directly on strong demand for fixed capital formation, have seen only a limited rebound since 2009.

The source of investment demand has changed, leading to a shift in the structure of investment in France. While real estate investment grew strongly in the early 2000s, it is now experiencing a downward adjustment, due in particular to the lack of resources available to local authorities. Investment items such as machinery, equipment, and transport infrastructure have seen a chronic decline in their share of gross fixed capital formation over the past 15 years. Conversely, the weight of intangible assets (which have no physical substance, such as training, advertising, software purchases, etc.) has increased thanks to the tertiarization of the economy. The demand for investment from service activities does not have the same structure as that from industrial or agricultural activities.

The lack of attractiveness of the French economy, caused by the deterioration of its cost and non-cost competitiveness, has led in some sectors to a reduction in direct investment (article on this subject on the BSI Economics website) by foreign companies in France in recent years. French companies themselves are increasingly choosing to locate their production sites abroad, as revealed by the external position of French economic investment. This expansion of French companies abroad helps to partially offset the external deficit generated by the deterioration of its trade balance, thanks to very positive asset income flows.

4. Towards a gradual rebound in investment from 2015 onwards?

Investment could begin to rebound in 2015 thanks to a combination of several factors. Weighed down for several years by the decline in the construction sector, which could come to an end in the coming quarters, investment could be relieved of this negative contribution (according to the outlook in the INSEE economic report of December 2014). Investment levels could also benefit from an improvement in the financial situation of businesses, which is expected to improve for two main reasons. Firstly, the fall in oil prices, which will reduce production costs. Secondly, tax cuts and reductions in social security contributions thanks to the rollout of the CICE (tax credit for competitiveness and employment) and the responsibility and solidarity pact, which should lower labor costs and boost corporate margins. Finally, corporate financing conditions continue to improve. In the markets, public and private bond financing is benefiting from the European Central Bank’s easing measures. With regard to bank financing, Banque de France surveys on corporate lending rates show historically low levels.

While there are reasons for hope, several obstacles to investment are likely to limit the extent of any possible rebound in investment in France in 2015. Companies can invest either to replace their working capital or to increase their production capacity. This desire to increase production capacity will be held back by weak capacity utilization indicators. In addition, companies could initially use the recovery in their margins to reduce debt, increase wages, or even distribute dividends. Finally, the persistent lack of momentum in domestic and European demand, and therefore in outlets, remains an obstacle to the recovery of investment.

Conclusion: patience…

In 2015, in addition to lower oil prices, the ramp-up of the CICE tax credit and the reduction in employer contributions will gradually free up companies’ capacity to invest in France. At the European level, investment will benefit from the implementation of the Juncker plan, which provides for the deployment of public funds to guarantee private investment. Despite these favorable factors, the recovery in investment is likely to be gradual, due to the financial situation of companies and governments, as well as weak demand and indicators of existing production capacity utilization.