Industrial policy in France (1/2)

How legitimate is industrial policy?

Summary

– A distinction must be made between deindustrialization and industrial decline. Deindustrialization is a historical stage of development that corresponds to a decline in industrial employment and industry’s share of GDP due to the shift to the service sector, productivity gains, and international competition. Economic policy cannot be used to combat these phenomena.

– On the other hand, industrial policy is legitimate in a situation of industrial decline, as in France, where French industries are suffering from an erosion of their competitiveness due to their mid-range positioning and insufficient margins. This industrial decline is affecting trade balances and causing France to lose market share internationally.

On September 12, 2013, 34 ten-year » action plans » for industry were presented at the Élysée Palace. With nearly €3.5 billion mobilized, the stated aim is to raise » the new industrial France to the highest level of global competition , » with the stated goal of producing €45.5 billion in additional added value over 10 years, exporting €18 billion more, and creating or strengthening 475,000 jobs. In a way, it was the » strategic state » that staged its grand political comeback.

September 12 is not an insignificant date: with the economic policy concepts it could bring into play ( « strategic state , » « Colbertism , » » industrial policy » ), it raises multiple issues relating to industrial and economic prospects and echoing the uncertainties of the French model. This return of industrial policy and the » strategic state » is not without its questions and even concerns. Over the past 20 years, French industrial policy has undergone a fundamental reorientation and today bears little resemblance to what it was in the 1960s and 1970s.

Its effectiveness, and even its legitimacy, are now being questioned. First and foremost, its effectiveness: for several decades now, a host of measures to support industry (research tax credits, competitiveness clusters, » grand emprunt » and investments for the future, etc.) have not been enough to halt the country’s » deindustrialization . » Its legitimacy is also being questioned, as this phenomenon of deindustrialization is widely analyzed as a historical trend linked to the shift to a service economy and the emergence of a » post-industrial society. » Furthermore, the past missteps of the » strategic state » mean that the return of this concept, which seems outdated, is viewed with caution.

We must therefore examine both what legitimizes public intervention in industrial matters (what is the legitimacy of industrial policy?) and then consider what industrial policy the French economy needs.

1. Deindustrialization: a historical process that does not necessarily justify public intervention through industrial policy

The phenomenon of deindustrialization can be characterized in two ways: it is both a decline in industrial employment as a share of total employment and a decline in industry’s share of GDP. France has lost nearly two million industrial jobs in 20 years, from 5.3 million in 1980 to 3.4 million in 2007, representing a structural decline of 36% that has accelerated since 2008. Furthermore, industry’s share of French GDP fell from 24% in 1980 to 14% in 2007, then to 12% in 2012.

1.1. A process affecting all developed economies

However, the mere existence of deindustrialization is not, in itself, a sign of economic and social difficulty. All deindustrialization is a historical trend in industrialized countries, in the sense that industry’s share of GDP tends to decline as development progresses. This can be observed in all advanced economies, even in Germany—the industrial model par excellence—where industry’s share of GDP fell from 27.4% in 1990 to 22.2% in 2007. The same is true in the United States (from 17.9% in 1990 to 14.1% of US GDP in 2007) and in all eurozone countries (from 22.6% in 1990 to 19.4% in 2007). The same trends, in similar proportions, can be observed in all advanced economies.

Deindustrialization is therefore not a trend specific to France, but common to all industrialized countries. Economic theory has even seen it as a historical evolution, an inevitable stage in the process of development and economic history. Augustin Landier and David Thesmar [1], for example, estimated that when the middle class reaches a certain income level (the estimate is a per capita income of $10,000 per year), its material needs are saturated and employment automatically shifts to services.

1.2. The causes of deindustrialization

In this sense, the causes of deindustrialization are not all problematic and do not justify public intervention through industrial policy. If an economy is deindustrializing, it is primarily due to the ever-increasing outsourcing of service consumption. Between 1980 and 2007, in France, Germany, and the United States, the number of jobs outsourced by industry to services more than doubled.

Certain traditional functions of industrial companies have been outsourced to service companies (transport, accounting, etc.), automatically leading to a sharp increase in the consumption of services by industry and, consequently, an increase in the share of business services in GDP, to the detriment of industry. According to the French Treasury, outsourcing accounts for 25% of job losses in the industrial sector over the past 20 years. But since, at the macroeconomic level, jobs are being created in a dynamic tertiary sector, where is the economic policy problem?

In other words, an economy that is deindustrializing is first and foremost an economy that is becoming more service-oriented: it is not so much industry that is declining as services that are growing. Deindustrialization and tertiarization theoretically go hand in hand. However, this is not a technological decline, since services invest and innovate as much as industries (60% of R&D jobs in France are in the service sector, regardless of whether they are in the private or public sector). Furthermore, services are just as much a driver of growth (98% of French growth in the 2000s was driven by services, according to Augustin Landier and David Thesmar).

On the other hand, productivity gains are structurally higher in the industrial sector than in services, which has the effect of relatively reducing the labor requirements to produce the same quantity of goods. If industrial jobs are declining, it is because industry is improving its productivity. Here again, there is no identifiable problem that could justify and legitimize an industrial policy.

A third « mechanical » cause of deindustrialization relates to changes in the structure of household demand, which is shifting toward services, considered « superior goods, » for which demand increases as households become wealthier and their level of equipment rises.

A fourth cause of deindustrialization is the subject of more political debate: international competition. The Treasury Department has estimated its contribution to industrial job losses in France between 1980 and 2007 at between 40% and 45%. Contrary to popular belief, only 17% of industrial job losses are linked to competition with emerging countries. The explanation lies in the fact that international openness is forcing French industry to specialize in sectors where it has comparative advantages, i.e., sectors that are intensive in skilled labor (pharmaceuticals, chemicals, etc.) at the expense of sectors that are intensive in low-skilled labor, hence the job losses.

Given this widespread historical trend, based on outsourcing, productivity gains, and integration into international competition, what legitimacy can an industrial policy aimed at combating this deindustrialization have when there is no economic justification for attempting to reverse the phenomena in question? Prevent the outsourcing of services? Restrict changes in the structure of household demand? Under these circumstances, why does deindustrialization in France pose an economic, social, and political problem?

2. French deindustrialization is a specific phenomenon. It corresponds more to a decline, the main symptom of which is the erosion of the competitiveness of French industries.

The legitimacy of industrial policy in France lies in the very specific nature of the deindustrialization facing the country. Not all deindustrialization is economically virtuous. The deindustrialization occurring in France is particularly marked. In this sense, a distinction must be made between » deindustrialization » and industrial decline. While deindustrialization is not in itself a sign of industrial decline, it can be in certain cases. This is the case in France, where deindustrialization is primarily a symptom of the weakening of the French productive fabric and its loss of competitiveness compared to its international competitors, starting with its German neighbor.

The findings of the Gallois report [2] are stark: with industry now accounting for only 12.5% of total GDP, France ranks only15th out of the 17 countries in the eurozone. According to the report, the country has lost 2 million industrial jobs in 30 years—which is not unique to France—but it has also lost considerable export market share, and its trade deficit reached a critical level of €72 billion in 2011. Above all, French industry has not recorded any productivity gains since the early 2000s.

2.1. The weaknesses of the French industrial fabric: insufficient innovation and mid-range positioning

Overall, French industries invest too little in technological innovation: 1.39% of GDP in 2009, compared with 2.01% in the United States and 2.02% in Germany. This is because sectoral specialization in France is not conducive to innovation. The industrial fabric is bipolar: on the one hand, there are high-tech companies, which invest heavily in R&D; on the other, there are low-tech sectors, which are overrepresented and invest very little in research and innovation.

In other words, the low level of R&D investment in French industry is largely linked to overall specialization in sectors that make fewer technological investments, and this unfavorable specialization has been worsening over the past decade.

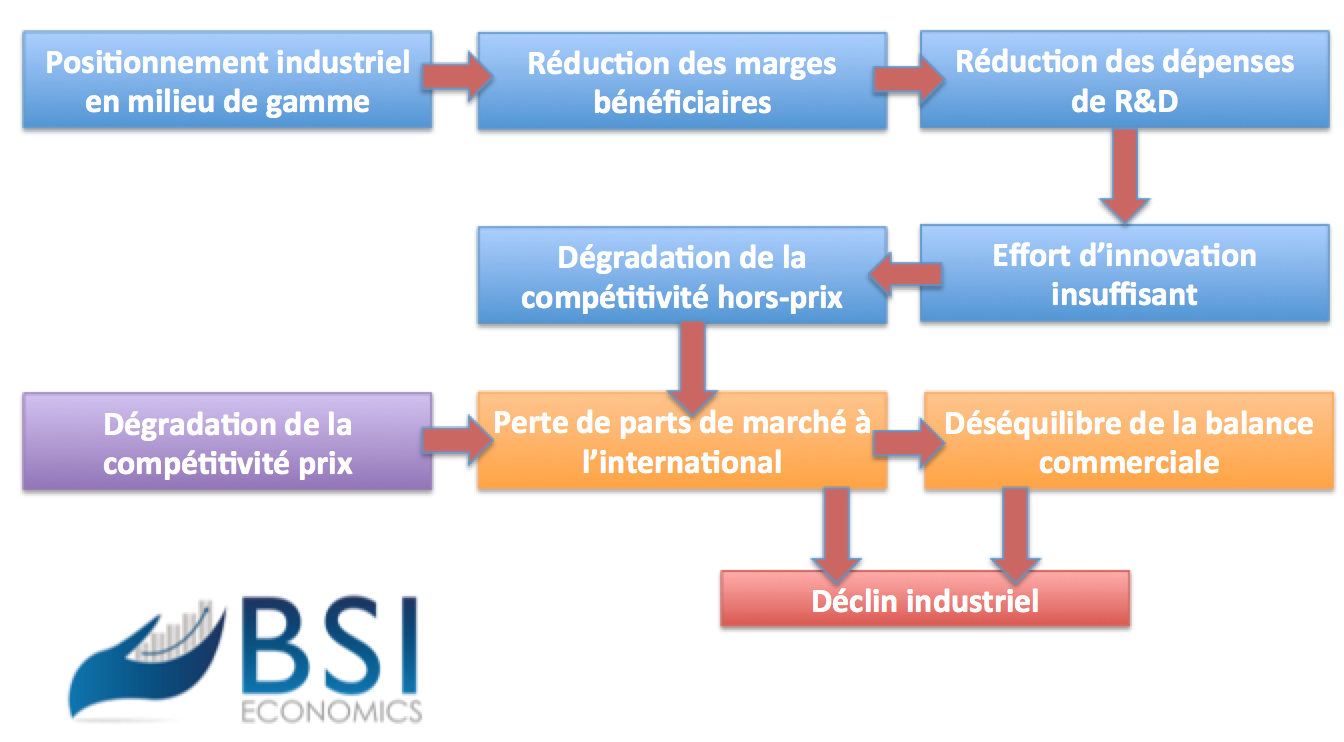

Under these conditions, French industry is more sensitive to international competition: with this positioning, generally in the mid-range, its exported products are more sensitive to price competitiveness than those of German industry, for example, which is firmly positioned in the high-end market and has set its sights on emerging markets.

To withstand international competition, French industrial companies must be able to justify higher prices by moving upmarket, with more innovative products and better service.

2.2. The decline in the competitiveness of French industrial companies

Competitiveness measures the ability of a country’s companies to participate in international trade. Beyond price competitiveness alone (a company’s ability to withstand price competition), it also covers a set of supply factors (quality, innovation, etc.) known as non-price competitiveness. However, in the 2012-2013 international competitiveness ranking published by the World Economic Forum, France fell from18th to21st place out of 144 countries studied.

The two main signs of this decline in French competitiveness are the widening trade deficit and the loss of export market share. This is particularly true in the industrial sector, where the balance of trade in manufactured goods fell from a surplus of €15 billion in 2002 to a deficit of €33 billion in 2011. In other words, it is mainly the poor performance of the export industry that is weighing on France’s trade balance, which has swung from a surplus of €25 billion in the 1990s to a deficit of the same amount in 2012.

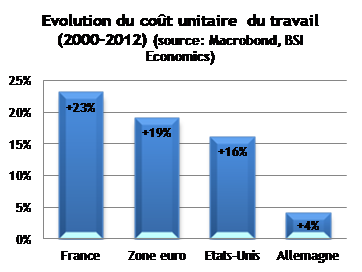

Until 2012, it was not so much price competitiveness that was the problem for France. In fact, it had deteriorated only slightly since 2008. The real problem was that the reduction in corporate margins was weighing heavily on non-price competitiveness.

In short, France’s » fall behind » Germany can be explained, to a large extent, by a decline in its non-price competitiveness. Non-price competitiveness encompasses a wide range of factors (brand image, product quality, adaptation to the local market, extent of the distribution network, capacity and credit constraints, etc.). However, as mentioned above, French industry is positioned in the mid-range, where it is difficult to differentiate oneself other than by price. The low level of the product range therefore weakens sales prices, reducing profit margins. This reduction in corporate margins limits their capacity for investment and innovation, thereby affecting their non-price competitiveness.

A new phenomenon is the recent deterioration in the price competitiveness of French industrial companies, which had remained stable until now. In several European countries, the structure of value added has been modified in favor of profits, with the share of the wage bill falling significantly, enabling companies to reduce their debt on the one hand, and to artificially maintain margins and generate productivity gains on the other, enabling them to achieve greater price competitiveness. This is particularly the case in Spain, Ireland, and Portugal, a strategy that is paying off in terms of international market share, but the price to pay is a dramatic rise in unemployment—on average 1.75 times higher than in France.

2.3. The link between industrial decline and trade imbalance is clear

» In the early 2000s, our industry produced more manufactured goods than French residents consumed. France then had a trade surplus, even after paying for its imports of energy and raw materials. Today, we produce fewer manufactured goods than we consume, so we import the difference and, in addition, we still have to import energy and raw materials, the prices of which have been rising since the early 2000s, » write Pierre-Noël Giraud and Thierry Weil [3] to summarize the situation.

The evolution of the trade balance is an indicator of industrial decline: a trade deficit suggests that the consumption of imported goods by a country is greater in value than the goods produced and exported by that same country. While some French industrial sectors have a largely positive trade balance (agri-food, aeronautics due to its very high technological content, chemicals, pharmaceuticals), most others are seriously in deficit. Since 2005, exporting sectors no longer compensate for the deficit of importing sectors. The trade balance has thus gone from a surplus of €25 billion in 2002 to a deficit of the same amount in 2011. One of the main reasons for this is the stagnation in manufacturing output over the last 15 years, while consumption has increased by 50% [4]. Ultimately, France exports high- and medium-tech products, but not enough to offset its imports of low-tech products.

It is in foreign trade that France’s decline lies: unlike Germany, whose industry has long been export-oriented, France has not taken advantage of the dynamism of emerging countries by selling them production equipment, automobiles, and related services, whose quality allows them to sell at a premium of 10 to 15%.

Conclusion

An industrial policy is legitimate and even necessary in France, given the specific nature of French deindustrialization, which is more a case of industrial decline than a » normal » transition to a post-industrial society. Beyond the principle itself, it remains to be determined which industrial policy is best suited to restoring industrial competitiveness, supporting innovation, restoring corporate margins, and initiating the necessary move upmarket.

Bibliography

– Pierre-Noël GIRAUD and Thierry WEIL, L’industrie française décroche-t-elle ? (Is French industry falling behind?), La Documentation française, 2013.

– Augustin LANDIER, David THESMAR, 10 idées qui coulent la France(10 ideas that are sinking France), Flammarion, 2013.

– Patrick ARTUS, Marie-Paule VIRARD, France without its factories, Fayard, 2012.

– Louis GALLOIS, Pacte pour la compétitivité de l’industrie française(Pact for the Competitiveness of French Industry), Report to the Prime Minister, November 5, 2012.

– Lettre Trésor-Eco No. 77, September 2010, The decline in industrial employment in France from 1980 to 2007: what is the

Notes

[1] Augustin LANDIER, David THESMAR, 10 idées qui coulent la France(10 ideas that are sinking France), Flammarion, 2013

[2] Louis Gallois, Pact for the Competitiveness of French Industry, Report to the Prime Minister, November 5, 2012.

[3] Pierre-Noël GIRAUD and Thierry WEIL, Is French industry falling behind?, La Documentation française, 2013

[4] Louis Gallois, Pacte pour la compétitivité de l’industrie française(Pact for the Competitiveness of French Industry), Report to the Prime Minister, November 5, 2012