Summary

– Generations that entered the labor market during the crisis have higher unemployment rates than previous , « more fortunate » generations.

– This effect is more pronounced for those with lower levels of education

– Economic theory is ambiguous about the long-term effects of poor conditions when entering the labor market

– The literature shows that the effects can be more or less long-lasting depending on location, level of education, and whether career changes are taken into account

Nearly six years ago, the global economy plunged into the most severe and persistent recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s. The financial crisis of 2008, followed by the sovereign debt crisis of 2010, led to a widespread increase in unemployment fueled by a large number of laid-off workers and five generations of young graduates (or dropouts). Every year, approximately 700,000 young people must convince employers of their abilities despite their inexperience. The economic crisis obviously makes this task more difficult.

The integration of young people during the crisis:

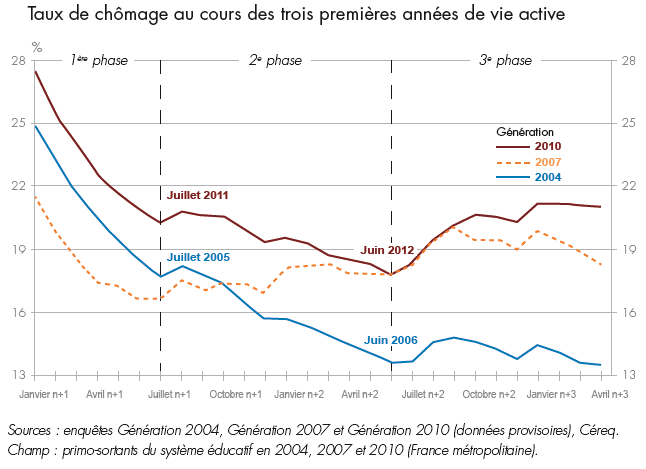

The generational surveys conducted by the Center for Research and Studies on Employment and Qualifications (Cereq) track the integration process of cohorts of young people entering the labor market every three years. In their latest survey, Barret et al. (2014) compare the integration of the 2004, 2007, and 2010 cohorts and clearly show the effect of the crisis on these young people’s access to employment. The graph below shows the unemployment rate in January of the year following graduation and in April three years after entering the labor market.

Sources: CEREQ Brief, BSI Economics

It shows first of all that unemployment is high for all generations (above 20%). We also see an initial phase of gradual decline in unemployment until the summer following the year of graduation. The second year is marked by a slowdown in the decline in unemployment for the 2004 and 2010 cohorts, while the 2008 crisis caused unemployment to rise for the 2007 cohort. However, during the third phase, characterized by stabilization of unemployment for the 2004 and 2007 cohorts, the dynamics of access to employment reversed and unemployment began to rise again for the 2010 cohort, which was hit hard by the continuing crisis in France. This generation thus entered the labor market with an unemployment rate 3 points higher than the 2004 generation and 6 points higher than the 2007 generation. The gap narrowed in the second phase with the 2007 generation, which was also affected by the crisis, but widened with the 2004 generation, which benefited from favorable economic conditions (the annual growth rate in 2004 was 3%, then 2% in 2005 and 2006 (World Bank)).The survey also reveals that the crisis had a significantly greater impact on unemployment among the least educated, but the quality of jobs (in terms of pay and type of contract) was not affected.

To get an idea of the longer-term differences, we can look at the generations affected by the 1993 recession.

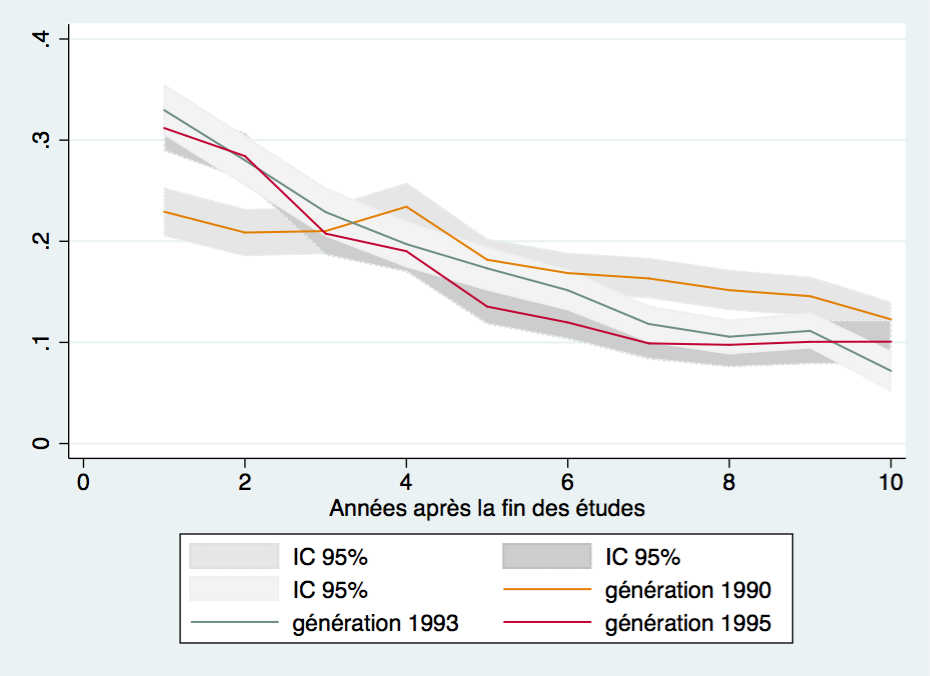

INSEE employment surveys show that the 1993 recession had a similar effect. The 1993 and 1995 generations began their careers with unemployment rates of over 30% in March of the year following their graduation, but this rate gradually declined over the next six years and then stabilized. The 1990 generation suffered from the 1993 recession, experiencing high unemployment rates for almost the entire period.

Unemployment rates based on potential experience for different generations

(sources: INSEE employment surveys, author’s calculations, BSI Economics)

Thus, a comparison of different generations reveals significant differences in the integration trajectories of young people depending on the economic cycle. Let us now consider the consequences of this phenomenon.

The theoretical effects of poor entry conditions on the labor market.

Economic theories offer different predictions about the impact of poor entry conditions. On the one hand, job search/job matching models generally predict that greater mobility leads to higher wage growth. Therefore, if a person experiences a period of unemployment or accepts a poor job but is able to return to a good job when the recession ends, they will only have lost a year or two of professional experience, which can easily be made up for through greater professional mobility. This theory of job shopping (Johnson, 1978) shows that a large part of wage growth occurs during the first years of experience due to frequent and rapid upward job mobility. Topel and Ward (1992) show that one-third of income growth in the first 10 years of working life is directly attributable to job mobility. According to this theory, a young person entering the labor market under poor conditions will accept a lower-quality job but will change as soon as the opportunity arises, more quickly and frequently than those who entered under better conditions. Through this more intense mobility, the model predicts rapid catch-up and therefore no long-term consequences of the conditions of entry into working life.

On the other hand, if finishing one’s studies during a recession leads to the accumulation of skills that differ from those acquired by more fortunate generations, then those affected will be less productive even several years after completing their studies, leading to a decline in long-term earnings. This human capital approach is compatible with a job search model such as that proposed by Jovanovic (1979). These models focus on the quality of the company/employee match and explain most of the dysfunctions of the labor market by allowing for different forms of friction. They go beyond the competitive framework and consider that labor suppliers and demanders operate in an environment of imperfect information, with heterogeneous supply and demand, transaction costs, and time-consuming job searches. Thus, when an individual enters a labor market in crisis, the number of job offers available to them is lower, which lengthens the duration of their search. It is then likely that the individual will not find a satisfactory job. Given the same experience, their salary will be lower because they have spent more time looking for and/or working in poor jobs (where they were less productive).

Furthermore, by working in lower-quality jobs, they have spent time accumulating poor forms of human capital that are too specific to the company (Jovanovic, 1979), the profession (Neal, 1999), or the task. Indeed, Gibbons and Waldman (2004) have shown that a worker who joins a company in difficulty is likely to be assigned to less demanding and lower-quality positions. As a result, their productivity does not increase as quickly as it should, and may be specific to certain tasks that they will no longer perform, which negatively affects their remuneration. To illustrate this idea, let’s imagine a graduate of an advertising school who is forced to accept a sales position when they graduate. During the months he spends doing this job, he will accumulate skills in negotiation and sales, but not in advertising. If he wants to return to work in this sector, he will not have accumulated the right type of human capital, which will negatively affect his chances of being hired and his salary. These models therefore predict persistent negative effects.

Finally, in the presence of information asymmetry, recruiters use all the information that candidates provide them as a signal of their level of productivity, including past salary levels. Thus, an individual who has been forced to accept a lower salary due to the crisis may suffer this effect in the long term. This is particularly evident in Devereux (2002), who uses the unemployment rate as a source of exogenous variation to explain variations in initial salary.

The results of empirical studies:

To determine the effect of poor entry conditions, researchers compare either individuals within a generation or differences between generations. In the first case, they look at the differences in trajectories between those who experienced a period of unemployment at the end of their studies and those who quickly found a job. These methods take into account the differences between the two groups. Identification lies in the difference within this cohort (intra-cohort variation) and estimates the persistence of unemployment at entry into the labor market,on income, or on the employment rate. This research generally finds very persistent negative effects (Gregg, 2001; Gregg and Tominey, 2005; Nordstrom Skans, 2011; Heylen, 2011). A person who experiences a period of unemployment at the beginning of their career suffers from a decline in wages for the rest of their career, in line with human capital and signaling models.

The second strategy consists of comparing not individuals within a generation but studying the differences between generations. This wave of literature therefore measures the impact of general entry conditions (most often measured by the unemployment rate of those under 25 in the year of graduation) on the employment rate and income based on experience. This line of research does not lead to such a clear conclusion. Genda et al. (2010) find that the unemployment rate in the year of graduation has a persistent (12-year) negative effect on the income of the least educated in Japan, unlike in the US, where these generations catch up with the more fortunate cohorts within three years. This result is largely due to the lower probability of obtaining stable employment caused by poor entry conditions. In the US, the effect is only temporary for high school graduates and slightly longer for college graduates. Kahn (2009) also finds a persistent negative effect of entry conditions on the income and employment of college graduates in the US (up to 15 years later). Hershbein (2011) finds that women who obtain their high school diploma during a recession participate less in the labor market than other lucky generations during the first four years. This result suggests a substitution of domestic production for labor market participation caused by the recession. In contrast, men tend to participate more. Oreopoulos et al. (2012) examine the quality of jobs found by young graduates entering the labor market in Canada and find that graduating during a recession has a negative impact on the employment rate and income of the affected generations. This effect persists for at least eight years.

In France, the only ones to have conducted this exercise (to our knowledge) are Gaini et al. (2012). Using data from INSEE employment surveys from 1982 to 2009, they find that the unemployment rate upon entering the labor market has a negative effect on income and employment rates in the short term, but that this effect disappears after three years.

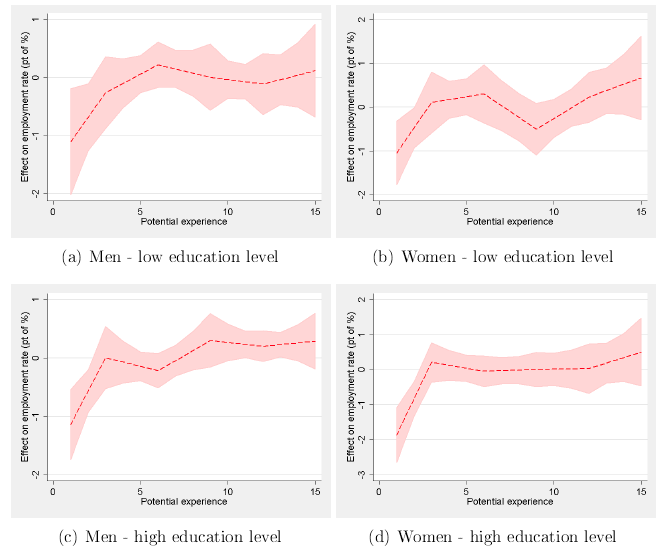

These results are illustrated in the figure below. They show the impact of a 1 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate at the end of studies on the employment rate, for different levels of education and by gender. For all four groups, an increase in unemployment at the time of entering the labor market reduces the employment rate of the affected cohort by approximately 0.1 percentage points. However, this effect is no longer significantly different from zero three years later.

Marginal effect of the unemployment rate at the end of studies on the employment rate according to the number of years after the end of studies

Sources: Gaini et al. (2012) BSI Economics

Why is France so unique?

Gaini et al. (2012) explain the difference between their results in France and the rest of the international literature by two reasons. First, a large proportion of the jobs created are at a level close to the minimum wage. As it is impossible to pay less than this level, all new hires are clustered around the minimum wage, regardless of whether the new employee has had bad experiences in the labor market in the past.

Second, since the youth unemployment rate is consistently very high (among the highest in Europe), past negative experiences are certainly not used by employers as an indicator of young people’s productivity. Poor entry conditions therefore have no long-term effect.

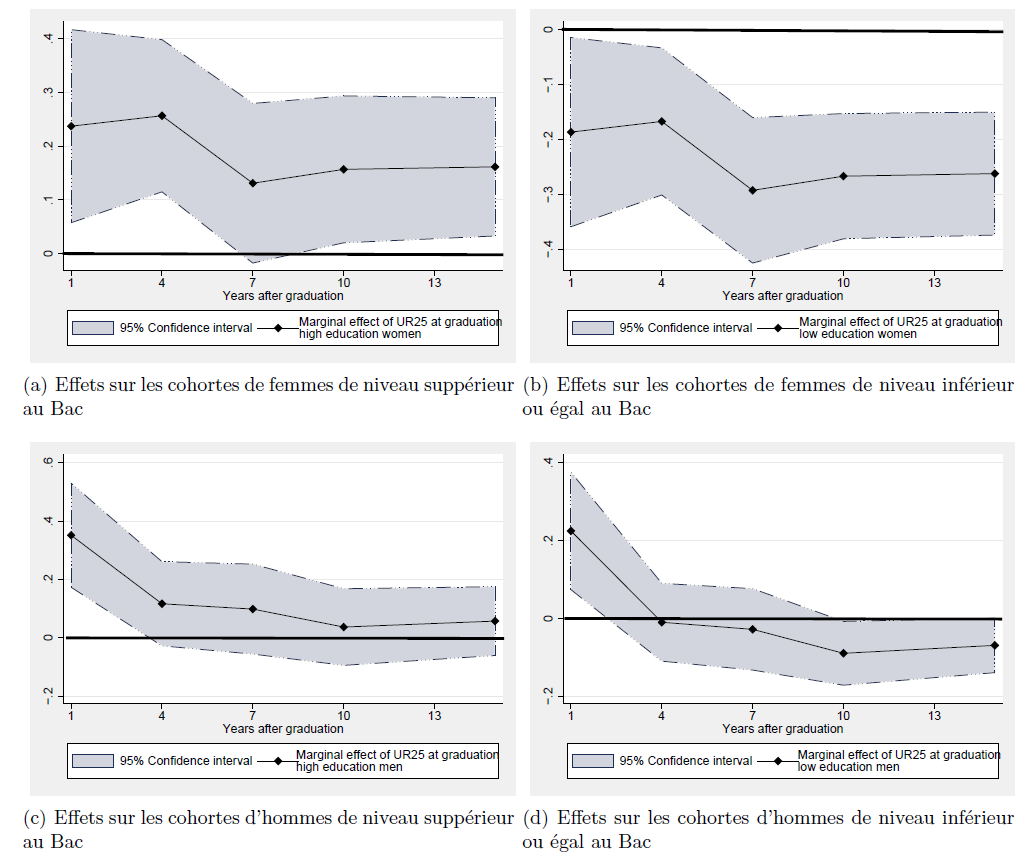

It is also possible that the lack of effect in France can be explained by a change in the career choices of young entrants. Indeed, the scarcity of jobs during recessions may force young graduates to accept low-skilled or low-paid jobs and thus abandon their initial strategies. This phenomenon is consistent with the literature on downward mobility (Forgeot and Gautié, 1997; Giret et al., 2006; Lize, 2005). In a manuscript written in 2013 (Heim, 2013)[1], we showed, using the same strategy and data as Gaini et al. (2012) that poor conditions for entering the labor market pushed men and women with a higher education level than the baccalaureate to seek refuge in public sector jobs, which are more protected than the private sector. However, the effect is negative for women with little education. The effect is permanent for women, while it disappears for men after four years.

Impact of a one-point increase in unemployment at the end of studies on the proportion of civil servants in a generation

Sources: Heim (2013), BSI Economics

These results reveal the attractiveness of public sector employment in France during times of crisis. However, as the number of positions is limited, it appears that the recession is leading to a change in the composition of successful candidates, with women with low levels of education being permanently displaced in favor of more men and women with higher levels of education. The non-permanent effect for men is probably due to a return to their initial career choices.

Conclusion

While theoretical models do not provide certain predictions about the effect of poor entry conditions on the labor market, econometric estimates tend to find a lasting detrimental effect on the employment rate and remuneration of the affected generations. France, however, seems to be an exception, as it appears that neither wages nor unemployment are affected in the long term by poor entry conditions.

However, these studies do not consider the changes in career paths caused by a recession at the end of studies. We have made a modest contribution to showing that unlucky generations tend to prefer the public sector in times of crisis (and permanently for women). This result clearly shows that if, overall, there are no differences in employment and income between lucky and unlucky generations in the long term, it may also be because they have changed their plans and strategies, and that this change may be permanent (particularly in the case of female graduates). Such results indicate that the unemployment insurance system—as secure as it may seem—does not guarantee the career paths of young entrants. It is therefore necessary to put in place a safety net to enable first-time entrants to secure their integration and allow them to access the jobs for which they have been trained.

During our research, we found the Belgian unemployment insurance mechanism particularly interesting (see Heylen 2011 for more information), whereby young graduates, even if they have never worked, can receive unemployment insurance for a period after the end of their studies, which is longer the higher their level of qualification. This mechanism aims to provide rapid unemployment insurance to the least qualified (and often most vulnerable) young people, and to provide security to those with higher degrees when they have been unable to find a job after several months. The level of insurance is just above the minimum social benefits so as not to discourage job seekers.

References:

– C. Barret, F. Ryk, and N. Volle. 2013 survey of the 2010 generation – in the face of the crisis, the gap between levels of education is widening. CEREQ Brief, 319:8, 2014.

– Paul J. Devereux. The Importance of Obtaining a High-Paying Job. MPRA Paper 49326, University Library of Munich, Germany, January 2002.

– Grard Forgeot and Jérôme Gautié. Professional integration of young people and the process of downgrading. Économie et Statistique, 304(1):53-74, 1997.

– M. Gaini, A. Leduc, and A. Vicard. A scarred generation? French evidence on young people entering into a tough labor market. Working papers of the DESE, Institut National de la Statistique et des Etudes Economiques, DESE, 2012.

– Yuji Genda, Ayako Kondo, and Souichi Ohta. Long-Term Effects of a Recession at Labor Market Entry in Japan and the United States. Journal of Human Resources, 45(1), 2010.

– Robert Gibbons and Michael Waldman. Task-specific human capital. American Economic Review, 94(2):203-207, 2004.

– Jean-François Giret, Emmanuelle Nauze-Fichet, and Magda Tomasini. The Downgrading of Young People in the Labor Market. Social Data – French Society, 2006.

– Paul Gregg. The Impact of Youth Unemployment on Adult Unemployment in the NCDS. Economic Journal, 111(475):F626-53, November 2001.

– Paul Gregg and Emma Tominey. The wage scar from male youth unemployment. Labour Economics, 12(4):487-509, August 2005.

– Arthur Heim. Public sector as shelter? The impact of graduating in a time of recession on selection into public employment. Master’s thesis, Paris School of Economics, September 2013.

– Brad Hershbein. Graduating high school in a recession: work, education, and home production. August 2011.

– Vicky Heylen. Scarring, effects of early career unemployment. Steunpunt werk en sociale economie., Leuven: HIVA – Katholieke Universiteit Leuven., 2011.

– William R. Johnson. A Theory of Job Shopping, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 92, No. 2 (May, 1978), pp. 261-278

– Boyan Jovanovic.Job Matching and the Theory of Turnover. Journal of Political Economy, 87(5):972-90, October 1979.

– Lisa Kahn. The long-term labor market consequences of graduating from college in a bad economy. Working paper, August 2009.

– Laurence Lize. Déclassement des jeunes et politique de l’emploi. Exploitation of the CEREQ’s « Generation 98 » survey. Cahier de la MSE 2005.17, 2005.

– Derek Neal. The Complexity of Job Mobility among Young Men. Journal of Labor Economics, 17(2):237-61, April 1999.

– Oskar Nordstrm Skans. Scarring Effects of the First Labor Market Experience. IZA Discussion Papers 5565, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), March 2011.

– Philip Oreopoulos, Till von Wachter, and Andrew Heisz. The Short- and Long-Term Career Effects of Graduating in a Recession. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 4(1):1-29, January 2012.

- Topel, Robert H & Ward, Michael P. Job Mobility and the Careers of Young Men, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 1992 MIT Press, vol. 107(2), pages 439-79, May