Summary:

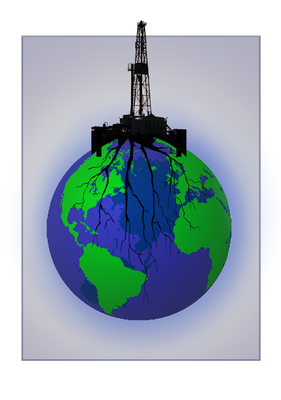

– Poland’s energy mix is dominated by fossil fuels, with coal accounting for nearly 50% of primary energy demand, oil 25%, and gas 12%.

– European commitments to reduce CO2 emissions, combined with a desire for independence from neighboring Russia, make it necessary to diversify the energy mix.

– In 2011, an American study estimated Poland’s shale gas reserves at 5,300 billion cubic meters, the largest in Europe, fueling the Polish political class’s dream of cheap domestic energy and prompting the Polish government to be a staunch pioneer in Europe in the exploration of these deposits.

– Initial drilling has so far proved disappointing, with the main companies (Talisman, Exxon, Total) deciding to suspend operations and withdraw. Furthermore, the Polish Geological Institute revised its estimates of exploitable volumes downwards in 2012, estimating reserves at between 350 and 770 billion cubic meters.

While many European countries, such as France, the Czech Republic, and the Netherlands, banned exploration mainly for environmental reasons, Poland bucked the trend and emerged as a fervent supporter of commercial shale gas development in Europe.

Supported by a very promising assessment of exploitable reserves made in 2011 by the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), Polish politicians believed they had found a solution to their energy dependence on their Russian neighbor and to the necessary move away from coal demanded by the European Commission.

However, the first drilling operations did not produce the expected results, reigniting speculation about the reproducibility of the American model and the direction of Polish energy policy, with underlying questions about the competitiveness of the domestic industry.

Polish energy policy under severe constraints

In addition to the challenge of low-cost energy, Poland’s enthusiasm for so-called unconventional gas can be explained by the need for Poland to change its energy mix for geopolitical, regulatory (the EU’s 20-20-20 target), and economic reasons. The energy mix is largely dominated by coal, of which the country has abundant reserves. According to data from the Polish Ministry of Economy for 2011, coal accounted for more than 50% of primary energy demand, followed by oil (25%), natural gas (13%), and biomass (6%).

However, when it comes to hydrocarbons, Poland remains particularly dependent on its Russian neighbor. According to data from the International Energy Agency, the country imports more than 90% of its oil and 60% of its gas from Russia. This is problematic given the latent geopolitical tensions between the two countries and the instability linked, among other things, to a delicate and sometimes unpredictable supply chain (notably the crisis with Ukraine in 2009). Several projects are underway to open up Poland and diversify its supply, including the construction of a liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal in the north of the country in Świnoujście, the increase in storage capacity, and the development of connections with neighboring networks (Germany, Czech Republic, Denmark, Slovakia).

Coal continues to dominate the electricity mix, accounting for nearly 90% of the country’s electricity production. This situation is problematic in view of the European targets for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (-40% compared to 1990 levels by 2030 in the latest Commission proposal). However, Poland refuses to rush out of its « all-coal » policy for the political reasons mentioned above, but also for economic and social reasons, largely overshadowing the environmental issue.

The competitiveness of its energy-intensive industry is partly based on the current low price of coal, hence its strong opposition to abandoning coal and its lack of cooperation in European negotiations to set ambitious targets. The environmental impact thus appears to be largely relegated to the background in the energy debate, attracting relatively little interest from the population and continuing to be perceived as an external obstacle to Poland’s economic development with a high social cost (the sector employs more than 125,000 people).

In addition, bringing coal-fired power plants up to standard would require significant investment in the short to medium term, weighing on the price and therefore the competitiveness of domestic energy. The implementation of carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies remains all the more costly given that Poland’s energy infrastructure is old (nearly 60% of power plants are over 25 years old and 44% are over 30 years old) and that coal accounts for nearly 70% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions.

Finally, this massive reliance on coal also raises questions about the sustainability of the model. Exploitable reserves are dwindling and the opening of new mines seems highly unlikely, given public opposition, the difficulty of obtaining new drilling permits, and the low profitability of these new mines according to the principle of diminishing returns, which states that with limited resources (in this case coal), an increase in production capacity leads to a smaller additional yield (because the most easily accessible mines are exploited first). It is estimated that at constant production levels, current reserves would last for around 30 years, with the first shortages appearing within 10 years. However, demand for electricity, supported by the country’s strong economic performance, shows no sign of slowing down (+1.5% on average between 2000 and 2009), while production has remained relatively stagnant (+0.6% per year over the same period). To meet this demand, the country has become a net importer of coal since 2009, once again raising the issue of energy independence.

The challenge of diversifying the energy mix is therefore a real one for Poland, not only in order to maintain its hard-won independence from Russia, but also to keep energy competitive and sustainable in order to support the country’s economic development. In this context, shale gas appears to be an attractive transitional energy source because it is less expensive than renewable energies and, unlike conventional gas, has the advantage of being produced on Polish soil.

Is shale gas a credible alternative?

In 2011, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) estimated Poland’s recoverable reserves of unconventional gas at 5,300 billion cubic meters, the largest basin in Europe representing nearly 300 years of reserves (based on 2010 consumption levels). However, the euphoria was short-lived. In March 2012, the Polish Geological Institute announced a range of between 350 and 770 billion cubic meters, which is 7 to 15 times less than the US estimate.

Determined to spearhead shale gas development in Europe, the Polish government nevertheless awarded more than a hundred exploration concessions for periods of 3 to 50 years. These were mainly granted to Polish groups (PGiNG, PKN Orlen, Lotos, and Petrolinvest), although major foreign groups are also present (Total, Exxon, Chevron, among others).

As of May 15, 2014, there were 80 active concessions (compared to 113 at the beginning of 2013), divided among 30 beneficiaries, with only 63 wells drilled. Several foreign groups, including Talisman, Marathon Oil, and Exxon, have already announced the suspension of their operations in Poland, citing insufficient volumes of exploitable gas, difficult drilling conditions, and regulatory uncertainty. This low number of wells is detrimental because it slows down the accurate estimation of available reserves and penalizes the future development of the sector.

Faced with the withdrawal of several investors, the government has amended two pieces of legislation governing the sector in order to create a more favorable economic environment. The first (geological law) aims to simplify the procedure for obtaining concessions, in particular by making it possible to obtain a prospecting/exploration and exploitation license for 10 to 30 years through a transparent tender process and, under certain conditions, without having to provide a detailed environmental study.

Prime Minister Donald Tusk also announced the abandonment of the creation of a national fossil fuel operator (NOKE) with mandatory equity stakes in all concessions. Finally, the Hydrocarbons Act creates a more attractive tax system for investors, with no specific tax until 2020. However, although these amendments are positive in terms of encouraging investors to continue drilling, they do not provide any assurance about the future economics of shale gas. Commercial exploitation requires efficient infrastructure, connection to the country’s main gas networks, and the possibility of competition.

Conventional or not, the Polish gas sector remains in its infancy and is currently unsuited to successfully replicating the American experience. To begin with, the network is hampered by its sparse coverage, with a large part of the country still poorly connected to the gas networks. According to the national statistics office, 54.6% of households did not have access to the gas network in 2012, which shows the scale of investment required. Currently, the network is much denser in the southeast of the country, due to its proximity to a large number of power plants, even though some potential unconventional gas basins are located in the north and east of the country.

Furthermore, competition on the gas network remains limited by market conditions. The state-owned company PGNiG accounts for more than 97.5% of gas sales in the country and manages the entire distribution network, rendering the free competition introduced in 2007 ineffective in the short term. Finally, the real impact on the economy and employment, considering the structure of the Polish market and the geological differences between deposits, remains unknown. Uncertainty persists, particularly with regard to the geological characteristics of the Polish subsoil and the costs of exploiting shale gas. As things stand, it is not certain that exploiting these resources will be cheaper than importing (particularly if better deals can be negotiated with Gazprom or supplies diversified with LNG deliveries from Qatar, for example). To overcome this relative lack of transparency, the British and Polish governments have nevertheless commissioned a joint study on the impact of shale gas development on their respective economies.

Conclusion

Far from the hoped-for windfall, the gains from shale gas exploitation appear highly hypothetical at present, depending both on the formation of a competitive gas market and on progress in accurately measuring unconventional gas resources.

However, the move towards a « globalization » of the gas market, linked to lower LNG transport costs and the rise of shale gas extraction technologies, could give Poland greater bargaining power with Gazprom and thus enable it to obtain cheaper hydrocarbons.

Finally, faced with this energy challenge, Poland is now also turning to Europe, calling for the creation of a genuine European energy union (based on six pillars, including a joint gas purchasing mechanism), which would enable it in the short/medium term to diversify its energy mix towards more gas while securing its supply.

References:

– Boersma, T., Johnson, C. (2012), Energy (In)security in Poland: the case of shale gas, Elsevier

– International Energy Agency (2011), Energy Policies of IEA Countries: Poland 2011, OECD Publishing.

– US Energy Information Administration (2011), World Shale Gas Resources: An Initial Assessment of 14 Regions Outside the United States.

– Resolution No. 202/2009 of the Polish Council of Ministers, (2009), Poland’s Energy Policy for 2030

– Su R. (2014), « Climate Conference: Has Poland Missed Its Chance? », Le Courrier de Pologne