This document has been drafted as part of our partnership with ANCRE.

As in most advanced countries, household consumption accounts for nearly half of France’s GDP, making it the largest component of demand. Consumption is also the most stable component of GDP, as a significant portion of household spending is devoted to essential needs (rent, insurance, energy, telecommunications), and these so-called » pre-committed » expenditures are not influenced by the economic cycle. For example, in 2009, during the financial crisis, GDP fell by 2.8% on average over the year, while household consumption held up, recording a slight increase of 0.3%. The Covid-19 crisis is the only recession during which consumption fell sharply due to administrative closures that prevented households from making their usual expenditures. Between thefourth quarter of 2019 and thesecond quarter of 2020, household consumption fell by 16.3% before rebounding by 18.4% in the following quarter.

1. Recent trends in household consumption

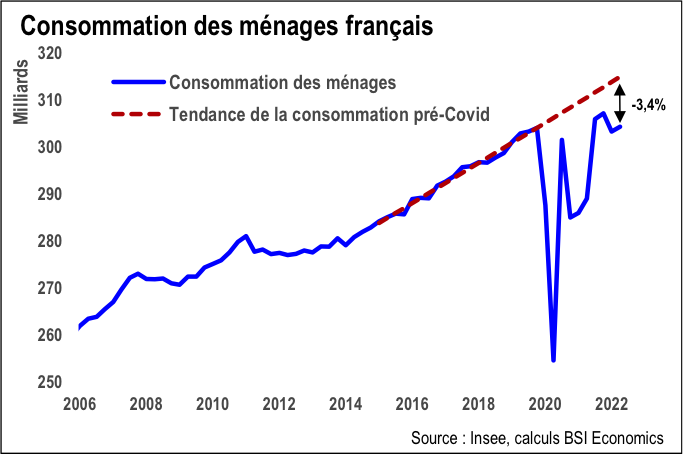

Since thethird quarter of 2021, household consumption has returned to its pre-Covid crisis level (i.e., that of thefourth quarter of 2019). Since then, consumption has stopped growing and has even declined slightly. Several factors are behind this stagnation, in particular supply difficulties that have constrained supply (in the automotive and electronic equipment sectors, for example) despite robust demand for these goods, and more recently a significant increase in consumer prices that has eroded household purchasing power.

Although consumption has returned to its pre-crisis level, it is still far from closing the gap with its pre-COVID trend (i.e., the rate of growth that would have prevailed without the health crisis) and is 3.4 percentage points below this trend in mid-2022. As in previous crises, it is possible that Covid will leave a permanent mark on household consumption and that the latter will never manage to close the gap with its pre-crisis trend.

2. Significant changes in consumption patterns

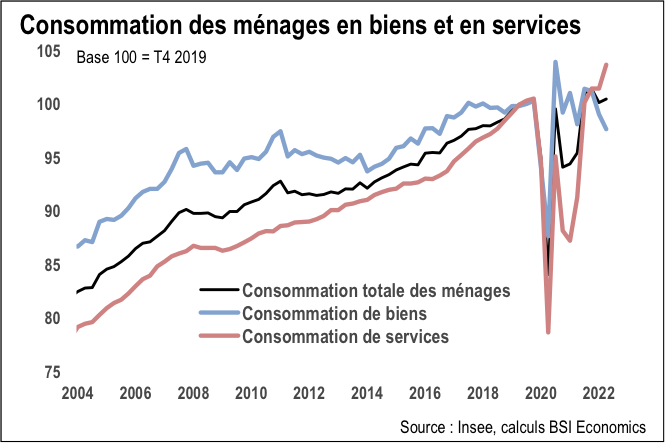

Covid-related restrictions have led to particularly marked changes in different types of household consumption. Household spending on goods has been much more resilient during the crisis and has rebounded much more strongly than consumption of services. The main reason for these differences is that businesses in the service sector (particularly leisure and recreation) were more affected by government closures than stores selling goods. In addition, online shopping allowed households to continue purchasing certain goods, which is not possible in the service sector.

A completely different trend has been emerging since the end of 2021, with service consumption booming, supported by the absence of restrictions, unlike goods purchases, which are suffering from multiple supply constraints affecting the industry.

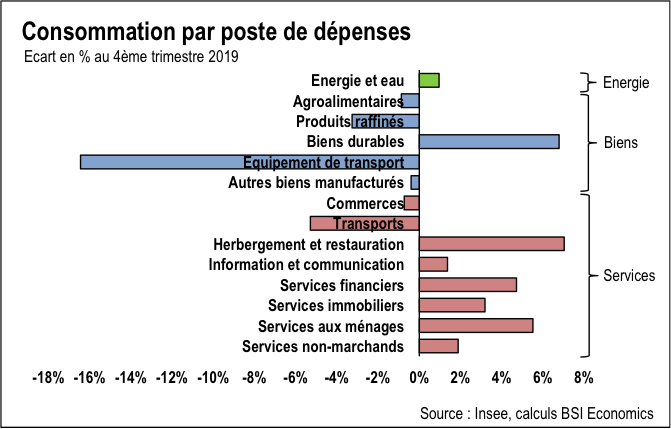

In detail, consumption of all manufactured goods is below its end-2019 level, except for purchases of durable goods. It is mainly spending on transportation equipment (automobiles) that is at a very low level. In terms of spending on services, only transportation spending remains depressed, while other areas, particularly accommodation, restaurants, and leisure, are at levels well above those at the end of 2019.

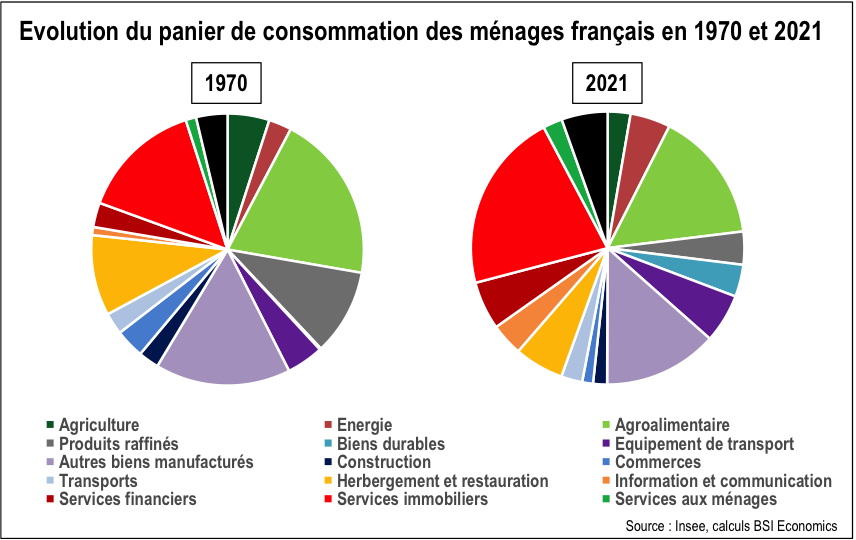

Changes in the composition of household consumption are not a phenomenon exclusive to Covid, although in this specific case, the shift has occurred at an accelerated pace. Between 1970 and 2021, the composition of household consumption has changed significantly. Spending on services now accounts for more than 52% of current household consumption, compared with only 45% in the early 1970s. Manufactured goods now account for 41% of household consumption, compared with 46% in 1970. French households now also spend a much larger share of their consumption on real estate and financial services, and conversely, a smaller share on hotels, restaurants, and transportation.

Finally, energy expenditure now accounts for just over 4.5% of total consumption, compared with only 3% in 1970. The current surge in energy prices is distorting the structure of spending. This is happening through two channels: an income effect and a substitution effect. Normally, when the price of a good increases, households are encouraged to substitute it with another good and thus postpone their consumption. However, energy is largely non-substitutable, so the only possible reductions in expenditure lie in energy efficiency. There remains the income effect, which leads households to reduce their non-energy expenditure because they have to pay more for the same amount of energy consumption. Ultimately, this should lead to an increase in the weight of energy expenditure in household budgets.

3. Outlook for household consumption

French household consumption is expected to increase slightly inthe third quarter before slowing down at the end of the year. This would be made possible by a rebound in household purchasing power in the second half of the year, thanks in particular to faster wage growth. In its economic update of September 7,INSEE forecasts thatpurchasing power will increase by +1.5% in the third quarter and then by +0.5% in the fourth quarter. Over 2022 as a whole, it is expected to remain flat compared with 2021 (+0% forecast).

However, short-term developments are surrounded by considerable uncertainty, as inflation forecasts are subject to significant uncertainty. Christine Lagarde, President of the Governing Council of the European Central Bank, recently pointed this out when she explained that the ECB itself « has made forecasting errors, and that these errors have been made by all forecasters. » The pace at which prices will change in the coming months will be decisive for consumption.

The initial signals from household economic surveys are not encouraging. Purchasing intentions are at an extremely low level, even lower than during the 2008 crisis. Only during thefirst lockdown in early April were households’ assessments of the advisability of making major purchases even lower. This is consistent with households’ statements about their financial situation, which is close to historic lows.

Furthermore, households’ savings intentions are well above their long-term average, which is unfavorable for consumption. The main reason is undoubtedly a desire to be cautious in the face of an unfavorable economic climate, even though at this stage households’ fears of unemployment remain limited (11 points below their long-term average).

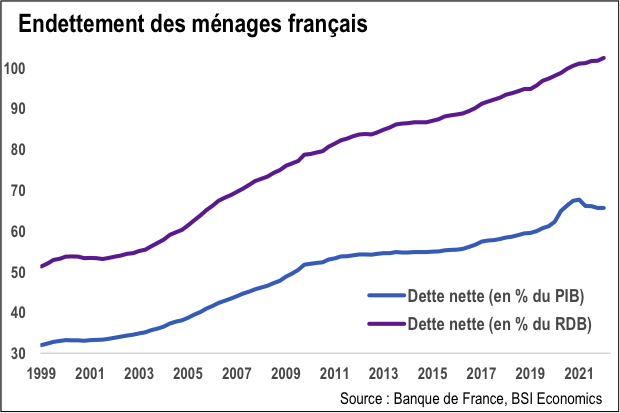

Household consumption expectations must also be viewed in the context of households’ financial situation, particularly their level of debt. The latter rose during the crisis, reaching 67.5% of GDP, before falling slightly to 65.5% since mid-2021. Current inflation is helping to ease the burden, as the outstanding principal is a fixed amount, while household incomes are rising in line with price increases. As a result, monthly repayments are accounting for an increasingly smaller share of household income. On the other hand, the monetary authorities’ response to this inflation, namely the rise in interest rates, is clearly reducing households’ ability to finance themselves through debt:

· On the one hand, lending conditions are tightening due to increased caution on the part of banks regarding the risk of insolvency.

· On the other hand, the rise in interest rates increases the cost of credit and reduces households’ financial leeway.

In the short term, as gross disposable household income is growing much more slowly than inflation and financing conditions are tightening, household debt is acting as a brake on consumption. Recent work bythe Swedish Central Bank shows that consumption falls even more sharply when interest rates rise if household debt is already high.

At this stage, the consensus anticipates limited growth in consumption in 2023, because despite dynamic gross disposable income (GDI), inflation will still be too high (the Bank of France forecasts an annual average of 4.7% in its latest macroeconomic projections) to lead to an increase in purchasing power (+0.2% forecast in 2023).

We will have to wait until 2024 to see consumption rebound (projected at +1.7%) thanks to lower consumer price growth (+2.7%), which will enable households to see their purchasing power improve significantly (+1.6%).