Erin Lin, How War Changes Land: Soil Fertility, Unexploded Bombs,

and the Underdevelopment of Cambodia, American Journal of Political Science, 2022

Abstract:

- Conflicts can have long-term consequences on agricultural productivity, particularly due to the problem of unexploded ordnance

- The most fertile areas, with generally loose soil, may be most at risk from this threat.

- In Cambodia, more than 30 years after the end of the bombing, the areas under cultivation are still smaller, less diversified, and less mechanized.

Armed conflicts can destabilize agricultural production in the countries involved and, more generally, agricultural markets. Russia’s war in Ukraine provides a recent illustration of this and raises fears of shortages (particularly of wheat) with dramatic consequences in countries such as Egypt and Lebanon. Unfortunately, the consequences of wars often outlive the signing of a ceasefire.

Armed conflicts can have long-term effects on agricultural production and on the populations that depend on agriculture for their livelihoods. Several recent studies have provided a better understanding of the mechanisms at work. This is the case in Erin Lin’s article (2022), which examines the consequences of the Vietnam War (1955-1975) on agricultural productivity in Cambodia. The author focuses in particular on the effect of bombs and explosives that did not detonate.

The trap of fertile soil

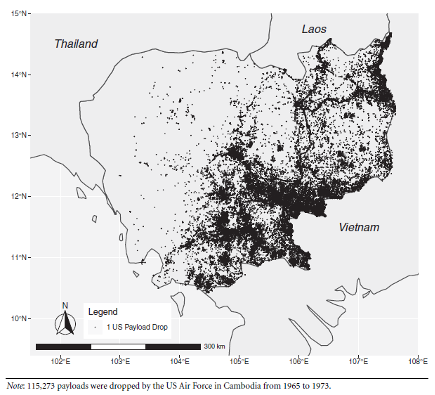

During the Vietnam War, and especially after 1969, the US armed forces carried out massive bombing raids on Cambodia, where the Viet Cong had built mobile bases. Erin Lin (2022) points out that in 1975, the US military dropped three times more bombs (in terms of tonnage) on Cambodia than it did on Japan during the entire Second World War. The scale of these bombings is also illustrated by Map 1, which shows more than 115,000 bombings between 1965 and 1973. These were often cluster bombs, multiplying the number of explosive devices hitting the ground.

Source: Erin Lin (2022).

Some of these bombs never exploded, giving rise to the problem of unexploded ordnance(UXO). This problem is not unique to Cambodia, with nearly a third of countries worldwide affected. The very high cost of land clearance operations generally limits the feasibility of such operations.

A crucial aspect of the problem is that the probability of non-explosion on impact depends on the type of soil the charge hits. In general, the probability of explosion is lower in loose soil (mud, sand, water, etc.). These types of soil also tend to be the most fertile. It is therefore in the most fertile and most heavily bombed areas that the risk of UXO is greatest for the population.

Impacts on farmers’ behavior

Erin Lin (2022) examines the consequences of these UXOs on agricultural productivity and the behavior of local populations. A farmer who knows that he lives in a high-risk area (because, for example, a neighbor once accidentally detonated a bomb) will logically change his behavior. They may concentrate their farming activities on a small plot of land (considered safe or previously cleared) or refuse to invest in heavy equipment (such as a tractor) that would increase the risk of detonating munitions buried in the ground.

The author suggests, based on interviews conducted in the field (in 2018, 40 years after the end of the conflict), that local populations are (a) aware of the risk posed by this munitions and (b) adapting their behavior. One woman explains that she prefers to use a machete to cut grass rather than buy a machine. Another explains that he only uses a small part of his land.

An econometric analysis makes it possible to measure more generally the impact of UXO on a set of variables relating to the behavior of farming households in 2012, more than 35 years after the end of the conflict. Schematically, the author distinguishes between households living in villages in two types of areas: the most fertile and the least fertile. He then measures the intensity of bombing around these villages. Two assumptions are necessary in order to interpret his results. First, the probability of non-explosion must be quasi-random after controlling for soil fertility. Second, since the author can only observe the intensity of the bombing (and not directly the presence of unexploded ordnance), the explosion of the bombs on impact must not cause any difference in long-term behavior. This second hypothesis is tested, as it would suggest a greater impact of bombing in areas with hard, and therefore less fertile, soil.

The author then shows that the effect of unexploded bombs can be substantial. For example, a farmer located in a fertile area bombed with average intensity will reduce the area of land he actively cultivates by 12% compared to a « similar » farmer in a fertile, unbombed area. Similarly, in areas most likely to have unexploded ordnance, the value of production per square meter of rice paddy is lower (suggesting less intensive production). Farmers tend to have fewer machines, diversify their activities less (for example, by fishing, which often requires them to move away from safe areas), and often spend more time away from their villages (see Figure 1 for an illustration of some of the results). This [HD5] reduces long-term productivity in areas that are otherwise the most fertile and contributes to keeping local populations in poverty.

Figure 1: The marginal effect of bombing on agriculture according to soil type.

Source: Erin Lin (2022). This graph shows the results of her analyses for the variables « % of land used, » « cultivated area, » « rice production, » « number of machines used, » and « share of harvest sold on markets » according to soil fertility. The implicit assumption for the last variable is that a lower proportion sold indicates an activity more geared towards subsistence farming.

Conclusion

Erin Lin’s article (2022) highlights a mechanism by which conflict can have long-term consequences on agricultural productivity: unexploded ordnance. This mechanism is not the only one. Conflicts can also cause direct soil pollution (e.g., the use of Agent Orange during the Vietnam War) or conflicts over property rights that can last over time (when farmers displaced by conflict return to their homes to find that their fields are being farmed by others).

While we must be wary of making hasty comparisons between the Ukrainian conflict and the Cambodian example discussed above, Erin Lin’s study shows that conflicts can have a long-term impact. However, this effect is not automatic, and government action to promote reconstruction can be of great help. Thus, historians—notably J.-M. Guieu (2015), drawing on the work of Hugh Clout (1996)—suggest that France’s agricultural production was able to return to its pre-World War I level by 1925, despite the extent of land devastated by the conflict (and unexploded shells).

References:

Hugh Clout, After the Ruins Restoring the Countryside of Northern France after the Great War, University of Exeter Press, 1996.

Jean-Michel Guieu, Gagner la paix 1914-1929(Winning Peace 1914-1929), La France Contemporaine (5), Edition du Seuil, 2015.

Erin Lin, How War Changes Land: Soil Fertility, Unexploded Bombs, and the Underdevelopment of Cambodia, American Journal of Political Science, vol. 66, 2022.

[1] As a reminder, Ukraine was the world’sfifth largest wheat exporter before the war began, behind Russia, Canada, the United States, and France. Its main customers were Lebanon, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Egypt. See the infographic created by Catherine Doutey for Courrier International.

C. Doutey, Wheat exports: which countries feed the world? Courrier International, April 9, 2022.

https://www.courrierinternational.com/grand-format/infographie-exportations-de-ble-quels-sont-les-pays-qui-alimentent-le-monde

[2] For example, if secondary targets that were bombed less were bombed more with defective equipment that was less likely to explode on impact, the study could be biased.

[3] The author uses U.S. military data on missions carried out by its air force to measure the intensity of the bombing.