Abstract :

· The climate change that is predicted could significantly threaten poverty eradication, particularly in Africa and South Asia.

· Climate change affects poverty through three main channels: declining agricultural production, increased frequency of natural disasters, and deteriorating health.

· It appears necessary to reconcile poverty reduction policies with climate change policies to prevent the situation from worsening. Concrete measures must be taken as quickly as possible.

At the end of this year, a new global agreement on climate change is expected at COP21 in Paris. This international climate conference is an opportunity to take stock of the consequences of climate change in terms of development and poverty. Without adequate measures to combat global warming, an additional 100 million people could fall below the poverty line by 2030 (World Bank, 2015). In this article, we will show that climate change poses a threat to poverty eradication.

Poor populations in developing countries will be hit hardest by climate shocks due to their geographical location, their heavy dependence on natural resources, and their lack of material resources to protect themselves against these risks. A 25-year survey of households in India conducted by Andhra Pradesh shows that while 14% of households manage to escape poverty, 12% end up falling back into poverty, 44% of them as a result of a climate shock (Krishna, 2006). Climate is a factor in many of the shocks that keep people in poverty. Climate change is likely to affect three factors responsible for poverty: deterioration in food security, increased frequency of natural disasters, and deterioration in health.

Climate change, food security, and poverty

Climate change significantly affects agricultural production systems through a decline in production, which threatens food security. Some of these effects are already observable in vulnerable regions, particularly in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where the majority of people living in poverty reside.

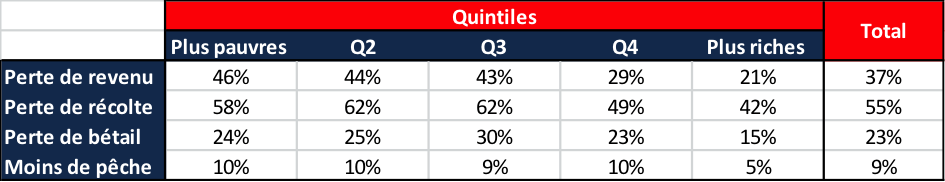

The fifth report of the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) dated November 2014 highlighted that climate change will lead to a decline in food production: crops are not adapted to respond to climate shocks (temperature variations and bad weather). While these impacts will remain relatively limited in the short term, without any adaptation efforts, the long-term consequences will be significant, particularly in tropical areas. According to the World Bank, by 2080, production could fall by 23% in South Asia, 17% in East Asia and the Pacific, and 15% in Africa (Havlík et al., 2015). This decline in production will threaten food security in countries where the situation is already worrying. Furthermore, as the agricultural sector employs a significant proportion of the national workforce, this will have a significant impact on poverty by generating substantial income losses (Table 1).

Table 1: Climate shocks and poverty in five countries (Wodon et al., 2014)

Percentage of households reporting economic impacts related to a climate shock

Source: Wodon et al. (2014)

Note: Study covering five countries in the Middle East and North Africa. Households report the impacts suffered from climate shocks over the past five years.

The decline in production following climate shocks will lead to higher food prices. Developing countries, mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where large poor populations are concentrated, will be most affected by this price increase. In the worst-case scenario, agricultural prices will increase by 12% by 2030 and 70% by 2080 in Sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank, 2015). In South Asia, the increase will be 5% by 2030 and 23% by 2080. As the poorest households already spend a significant proportion of their income on food (Figure 1), it is unclear whether they will be able to cope with such price increases as consumers. They will probably have to reduce their food consumption to the detriment of their health unless the state intervenes and subsidizes agricultural production, which will increase public spending. If no policy measures are taken, a 10% increase in food prices would result in a 72 kilocalorie reduction in daily calorie intake (Green et al. 2013).

Graph 1: Share of total consumption spent on food and beverages by region and consumption level (2010)

Source: Author using World Bank data (2010)

For agricultural producers, the price increase could translate into higher wages and profits. This is a significant effect when, for many poor households, agriculture is a source of income (World Bank, 2015). In the long term, only a small portion of the population will benefit from these price increases, while the rest of agricultural workers will be forced to find other means of subsistence by moving to more lucrative sectors of production. This could lead to rural exodus and a significant change in the structure of the economy.

Poor households would therefore face two opposing effects of price increases: a positive effect on agricultural profits (for agricultural producers) and a negative effect on consumption (for everyone). However, most studies agree that the overall impact will be negative. A study conducted by Ivanic and Martin (2014) shows that a 10% increase in food prices will lead to an average increase of 0.8 percentage points in the extreme poverty rate in the short term, although the situation varies from country to country (Figure 2). Past episodes confirm this relationship between rising agricultural prices and poverty. The global rise in food prices between June and December 2010 (average increase of 37%) led to an increase of 44 million people living in extreme poverty (Ivanic, Martin, and Zaman, 2012).

Figure 2: Impact of a uniform 10%, 50%, and 100% increase in food prices on poverty

Source: Author using results from the study by Ivanic and Martin (2014).

Poor non-agricultural households will be the most affected because they will not benefit from the positive effects of the price increase. Thus, the rise in food prices resulting from climate change will increase poverty rates among non-agricultural households by 20% to 50% in Africa and Asia (Hertel, Burke, and Lobell, 2010).

A few measures can be taken to limit the negative impact on food security. Improving infrastructure and increasing access to local and international agricultural markets can help offset production shocks linked to climate change. Thus, opening up to global markets (e.g., lowering customs duties) and any measures that reduce the isolation of regional markets (e.g., building roads) could limit the consequences of local production shocks (Ndiaye, Maitre d’Hôtelet le Cotty, 2015). Improving agricultural practices and crops by making them more resistant to climate change is also necessary. This can be achieved through the use of more suitable fertilizers, the development of polyculture to strengthen crop resistance, or the improvement of irrigation systems (in the event of drought). Finally, to avoid long-term impacts, it is essential to rethink the current use of forests and agricultural land, which are now a primary source of CO2 emissions in poor countries (World Bank, 2015).

Climate change, natural disasters, and poverty

With climate change, natural disasters will become more frequent. Changes in temperature and precipitation will increase the frequency of floods, droughts, and heat waves (IPCC, 2013; World Bank, 2015).

Natural disasters are a factor that exacerbates poverty. In Bangladesh, for example, after Cyclone Aila struck the subdistrict of Shyamnagar, the poverty rate (population living on less than $1.25 per day) rose from 41% to 63% between 2009 and 2010 (Akter and Mallick, 2013). For the poorest households, the consequences of natural disasters tend to persist over time (World Bank, 2015). Following a natural disaster, children from the poorest families drop out of school and rarely return, which undermines their future income. Poor households exposed to climate shocks tend to invest in less risky and less profitable assets, which keeps them in poverty.

Risk areas are inhabited by both wealthy populations and poorer households. These regions can offer economic opportunities that attract wealthy households. For example, proximity to the coast means lower maritime transport costs, and regular flooding can increase agricultural productivity (Loayza, et al., 2012). However, real estate prices in these regions are relatively low and often attract disadvantaged populations. These areas therefore have a concentration of both wealthy and poor populations. A recent World Bank report (2015), combining data from various sources in 52 countries, concludes that poor people living in West Africa are more exposed to flooding than their wealthier neighbors. Their conclusions on the risk of drought are even more alarming. In most countries in Asia, South Africa, and East Africa, poor households are more exposed to droughts.

On average, poor people are therefore more vulnerable to natural hazards and, when affected, they lose more than their wealthier counterparts (World Bank, 2015). A study in Bangladesh showed that poor households affected by flooding lost 42% of their household income, compared with only 17% for other households also affected by flooding. There are several reasons for this difference.

First, the losses suffered are greater for disadvantaged populations because they own lower-quality and more vulnerable assets. Poor households invest more in assets in kind, such as livestock, which are more vulnerable to climate shocks (Nkedianye et al. 2011). In contrast, wealthier individuals tend to invest in higher-quality housing and financial assets. Poor households live in poor-quality housing (houses made of wood, bamboo, mud) that will suffer greater damage in the event of flooding.

As mentioned above, poor people are more dependent on agriculture for their livelihoods and as a source of income. However, natural disasters have a significant impact on agricultural systems (World Bank, 2015). Following a natural disaster, food prices rise. For example, 10 months after Hurricane Agatha struck Guatemala in 2010, food prices had risen by 17% (Baez et al. 2014). Poor populations are more sensitive to these price increases (World Bank, 2015).

Finally, natural disasters also have an impact on health and education, which is greater among poor populations. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, after climate shocks, poor households reduced their children’s nutritional intake and cut back on medical visits (Alderman, Hoddinott, and Kinsey, 2006; Dercon and Porter, 2014). Children affected by floods are also less likely to finish primary school (Alderman, Hoddinott, and Kinsey, 2006; Dercon and Porter, 2014).

Policy measures can be taken to limit the negative impact of climate change-related natural disasters on poverty.

As we have seen, poor people live in high-risk areas primarily because of the cost of rent. Rent control policies could help develop safer areas. Lack of access to adequate infrastructure explains why poor people suffer more during natural disasters. For example, the lack of drainage increases the damage caused by flooding. To remedy this, countries need to invest more in infrastructure in high-risk areas. The types of investment needed also need to be rethought. New infrastructure must be able to withstand future climate change. Investing in protective infrastructure such as dykes could help households cope with climate hazards. Such projects are already underway in some countries around the world, such as the World Bank’s water supply project in Lima. Schools and hospitals must also be able to withstand natural shocks. For example, a « SafeHospitals » project has been set up by the WHO, the International Strategy for Disaster Reduction, and the World Bank.Developments can enable the homes of the poorest people to withstand climate shocks, as they are currently particularly vulnerable to flooding and landslides. Simply banning settlement in these areas could have an adverse effect by forcing poor populations to settle in even more vulnerable areas and in an informal manner. Land use regulations need to be supplemented by investments that would enable poor people to settle in safer areas while retaining their jobs and adequate services. Improving access to financial services via mobile accounts, for example, would help reduce the impact of natural shocks on the poorest. Finally, prevention, monitoring, and evacuation measures can also be useful.

Climate change, health, and poverty

The third channel linking climate change and poverty is health. Climate change will have health consequences for the poorest populations and vulnerable groups such as children and the elderly. Health problems are a major source of poverty. In Kenya, 73% of households reported that health expenses were one of the main reasons for their poverty (Krishna et al. 2004). Poor people are more affected by health shocks because they have fewer resources available to devote to prevention and because they only have access to poor-quality health systems. The poorest households do not have social safety nets that would enable them to cope with these shocks (Watts et al., 2015). Health shocks limit productivity and contribute to lower incomes and higher health expenditures, which is yet another obstacle to poverty reduction.

Climate change will exacerbate the prevalence of certain diseases among the poorest households. For example, rising temperatures promote the emergence of vector-borne infectious diseases such as malaria (Siraj et al., 2014). A rise of 2 or 3 degrees Celsius could lead to the spread of malaria to an additional 150 million people (WHO, 2003).

The consequences of climate change on food production and the natural disasters described above are forcing poor people to reduce their calorie intake, which is an obstacle to eradicating malnutrition.

Heat waves associated with global warming (IPCC, 2014) primarily affect poor populations due to their poor living conditions, poor quality housing, and lack of access to air conditioning. These heat waves are likely to significantly reduce the productivity of workers, who will suffer income losses (Seppänen, Fisk, and Lei, 2006).

In addition to the necessary improvement of health infrastructure and increased access to education, particularly for women, concrete measures can help limit the impact of climate change on poverty through deteriorating health. The World Bank (2015) therefore recommends the rapid implementation of a universal health care system to enable the most vulnerable people to protect themselves against these risks.

Conclusion

The consequences of climate change could therefore be disastrous for the poorest populations. However, this situation is not inevitable. It is important to put in place social protection systems that are highly responsive and capable of mobilizing in times of crisis. Developing health coverage for the most vulnerable populations will prevent climate change from deteriorating the health of the poorest. In the agricultural sector, improving and changing production techniques will limit the decline in production while respecting the environment.

These policies must go hand in hand with measures to reduce CO2 emissions. These policies, which come at a cost in terms of investment and energy, must be designed so as not to slow down poverty reduction in the short term. Redistribution policies and the establishment of social protection systems could enable governments to protect the poorest. A carbon tax, for example, could generate additional resources to increase social protection and finance development-related infrastructure investments.

These measures must be taken by 2030 before the impacts of climate change become too severe. The COP21 negotiations must help to eradicate poverty.

Sources

Akter, S., and B. Mallick. 2013. “The Poverty– Vulnerability–Resilience Nexus: Evidence from Bangladesh.” Ecol.Econ. 96 : 114–24.

Alderman, H., J. Hoddinott, and B. Kinsey. 2006. “Long-Term Consequences of Early Childhood Malnutrition.” Oxf. Econ. Pap. 58: 450–74.

Baez, J., L. Lucchetti, M. Salazar, and M. Genoni. 2014. Gone with the Storm: Rainfall Shocks and Household Wellbeing in Guatemala.Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank, 2015, “Shock Waves: Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty”

Boschung, A., Nauels, Y., Xia, V., Bex, and P. M. Midgley, 1–30. Cambridge, U.K. and New York: Cambridge University Press. Jensen, R. 2000.

Dercon, S., and C. Porter. 2014. “Live Aid Revisited: Long-Term Impacts of the 1984 Ethiopian Famine on Children.” J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 12: 927–48.

Green, R., L. Cornelsen, A. D. Dangour, R. Turner, B. Shankar, M. Mazzocchi, and R. D. Smith. 2013. “The Effect of Rising Food Prices on Food Consumption: Systematic Review with Meta-regression.” BMJ 346 : f3703.

Havlík, Petr; Valin, Hugo Jean Pierre; Gusti, Mykola; Schmid, Erwin; Forsell, Nicklas; Herrero, Mario; Khabarov, Nikolay; Mosnier, Aline; Cantele, Matthew; Obersteiner, Michael; November 2015; “Climate change impacts and mitigation in the developing world: an integrated assessment of the agriculture and forestry sectors (English),” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, WPS7477

Hertel, T. W., M. B. Burke, and D. B. Lobell. 2010. “The Poverty Implications of Climate-Induced

Crop Yield Changes by 2030.”Glob. Environ. Change, 20th Anniversary Special Issue 20:577–85.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). 2013. “Summary for Policymakers.”In Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, edited by T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, G.-K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S. K. Allen, J.

Ivanic, M., and W. Martin. 2014. “Short- and Long-Run Impacts of Food Price Changes on Poverty.” Policy Research Working Paper 7011, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Ivanic, M., W. Martin, and H. Zaman. 2012. “Estimating the Short-Run Poverty Impacts of the 2010–11 Surge in Food Prices.” World Dev. 40: 2302–17.

Krishna, A., P. Kristjanson, M. Radeny, and W. Nindo. 2004. “Escaping Poverty and Becoming Poor in 20 Kenyan Villages.” J. Hum. Dev. 5: 211–26.

Loayza, N. V., E. Olaberria, J. Rigolini, and L. Christiaensen. 2012. “Natural Disasters and Growth: Going Beyond the Averages.” WorldDev. 40 (7): 1,317–36.

Ndiaye, M., E. Maitre d’Hôtel, and T. Le Cotty. 2015. “Maize Price Volatility: Does Market Remoteness Matter?” Policy Research Working Paper 7202, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Nkedianye, D., J. de Leeuw, J. O. Ogutu, M. Y. Said, T. L. Saidimu, S. C. Kifugo, D. S. Kaelo, and R. S. Reid. 2011. “Mobility and Livestock Mortality in Communally Used Pastoral Areas: The Impact of the 2005–2006 Drought on Livestock Mortality in Maasailand.” Pastoralism 1 : 1–17.

World Health Organization, 2003. Summary Booklet: Climate Change and Human Health – Risks and Responses. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Seppänen, O., W. J. Fisk, and Q. Lei. 2006. Effect of Temperature on Task Performance in Office Environment. Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Siraj, A., M. Santos-Vega, M. Bouma, D. Yadeta, D. R. Carrascal, and M. Pascual. 2014. “Altitudinal Changes in Malaria Incidence in Highlands of Ethiopia and Colombia.” Science343: 1,154–58.

Watts, N., W. N. Adger, P. Agnolucci, J. Blackstock, P. Byass, W. Cai, S. Chaytor, T. Colbourn, M. Collins, A. Cooper, P. M. Cox, J. Depledge, P. Drummond, P. Ekins, V. Galaz, D. Grace, H. Graham, M. Grubb, A. Haines, I. Hamilton, A. Hunter, X. Jiang, M. Li, I. Kelman, L. Liang, M. Lott, R. Lowe, Y. Luo, G. Mace, M. Maslin, M. Nilsson, T. Oreszczyn, S. Pye, T. Quinn, M. Svensdotter, S. Venevsky, K. Warner, B. Xu, J. Yang, Y. Yin, C. Yu, Q. Zhang, P. Gong, H. Montgomery, and A. Costello. 2015. “Health and Climate Change: Policy Responses to Protect Public Health.” The Lancet.

Wodon, Q., A. Liverani, G. Joseph, and N. Bougnoux. 2014. Climate Change and Migration: Evidence from the Middle East and North Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank.