Summary:

– The structure of innovation financing reveals a market failure by depriving economic actors of the necessary means to develop and finance innovation at each stage of its life cycle.

– Efforts by public authorities to guarantee innovation financing can cause imbalances by directing financing towards the least profitable and most risky segments of innovation.

– The decline in companies’ self-financing capabilities and the budgetary constraints weighing on governments are a threat to the viability of the innovation financing model in advanced economies, including France.

Innovation is often presented as a major challenge for sustainable growth in advanced economies. In this era of globalization, the concept of business competitiveness is central to the concerns of all economic actors, and as the main driver of non-cost competitiveness, innovation is proving to be essential in the international economic landscape.

The shift of developed economies towards the knowledge economy has placed the concept of innovation at the heart of global growth issues, and initial reflections on this concept have highlighted the difficulty of defining innovation. It is in this context that the Oslo Manual[1]defined four types of innovation: product, process, marketing, and organizational. Although these are very different, each of the processes that lead to innovation is long, unpredictable, and difficult to control. Nevertheless, when successful, they lead to major technological, economic, and/or social advances and become powerful accelerators of growth. These specific characteristics raise questions about how innovation should be financed.

A specific financing structure

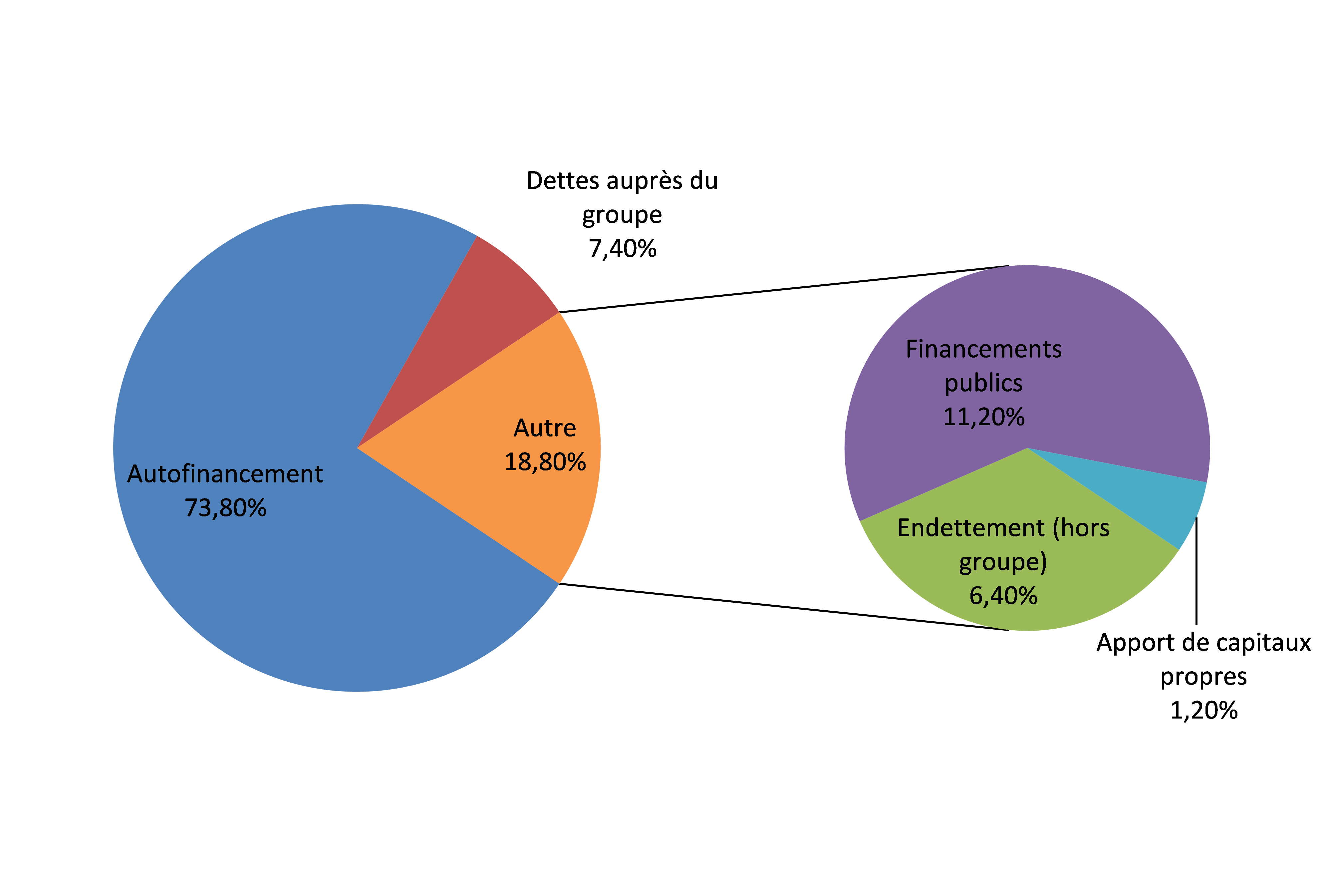

According to a survey by INSEE[2], self-financing appears to be the main source of funding for technological innovation. This method of financing, given that the associated cost is limited to an opportunity cost, is preferred because it is less expensive than bank financing, where the risk premiums charged can be high.

Structure of financing for technological innovation in France

Sources: FIT survey – Sessi, BSI Economics

However, self-financing is only possible for companies that are sufficiently capitalized and have sufficient self-financing capacity to devote a significant portion of it to financing innovation. Given the downward trend in companies’ self-financing capacity since the crisis, this type of financing may be more difficult to mobilize. The self-financing rate[3]of French companies reached 64.3% in September 2013[4], compared with nearly 100% in the euro zone. This low rate is due in particular to the low margins generated by non-financial companies based in France.

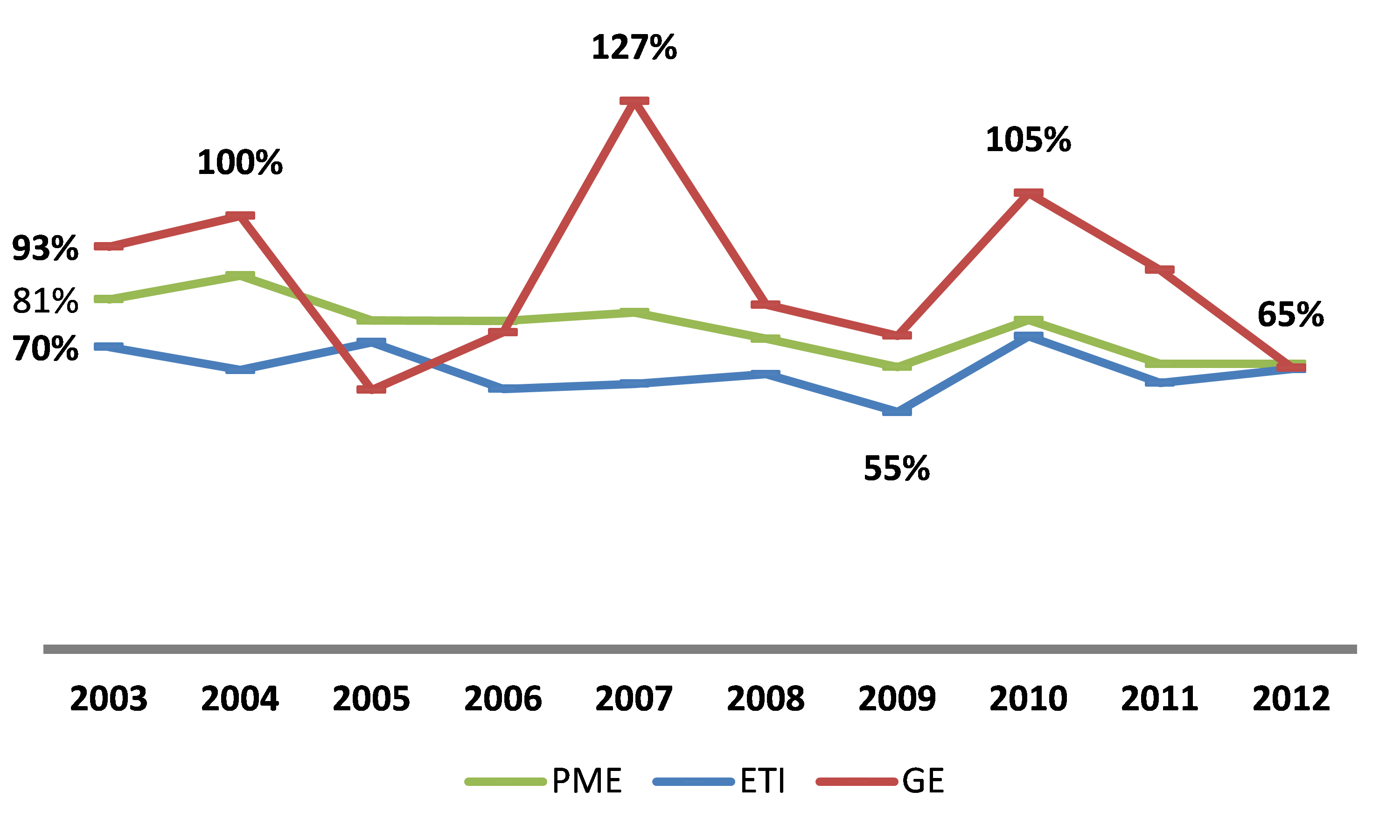

Debt owed to the group, which accounts for more than 7% of technological innovation financing, only concerns companies belonging to a group. However, the majority of innovative companies today are independent[5]. This type of financing is perfectly substitutable for self-financing, but the decline in self-financing rates affects all companies, even the largest ones. Although self-financing is structurally weaker when companies are small, the self-financing rate at the end of 2012 was consistent across all company sizes.

Average self-financing rate by company size

Sources: Webstat, Banque de France, BSI Economic

Companies’ limited access to self-financing hinders research and development of the most radical innovations

The use of internal resources is therefore possible for companies that have reached a critical size, are firmly established in their market, or are multi-sectoral, with activities that are generally international in scope. However, the latter are subject to what Clayton M. Christensen[6]has identified as « the innovator’s dilemma. » In his book, the author argues that innovations, which he defines as disruptive—i.e., innovations that are intended to expand the market to new customers not yet served by existing technologies—cannot come from the initiative of the largest companies because their development is too costly.

Disruptive technology is new technology whose scope is highly uncertain and costly at every stage of its development (research, launch, industrialization, and commercialization). Ultimately, if successful, it undermines existing technologies, which are those from which companies derive profits and, in most cases, hold economic rents.

In addition, the internal human resources of these large companies are trained to develop their market, anchor their positioning, and monitor the competition, ensuring that they preserve or improve their company’s position in a competitive environment. The management in place is therefore generally ineffective at innovating and will not be able to build and develop teams capable of effectively developing large innovative projects, especially when it comes to getting them off the ground.

These arguments support the idea that there is a failure of self-financing in the funding of the most daring technologies.

Traditional bank financing is unsuitable for financing innovation

The weight of bank financing in external sources of financing for technological innovation appears to be very low. In fact, it accounts for one-third of innovation financing, while representing more than 80% of external financing for businesses[7]. The absence of bank intermediation in innovation financing is justified by the innovation life cycle and the specific characteristics of the French banking system.

Innovation is a long process. The implementation of the resources necessary for creation and the uncertainty surrounding the market prospects for innovations effectively deprive the most fragile structures of bank financing in the earliest stages of new technology development. Granting credit based on borrowers’ future repayment capacity is impossible for young companies planning to develop new products or services for which no market research can credibly predict the outcome.

Innovation is a process that is difficult to control. And the French banking system does not have the tools to monitor the technology of the companies it finances. However, this is essential in order to encourage entrepreneurs to implement the best possible measures for developing innovation.[8]. Unlike the German Haus bank system, which gives German banks an important role in financing businesses by providing, in addition to credit, a range of services that enable them to monitor businesses closely and gain a better understanding of their environment and financial situation, the French banking system is characterized by more stringent requirements for collateral associated with the loans it grants. This weak relationship between lenders and borrowers creates greater uncertainty about the projects to be financed and therefore a greater risk of default, all other things being equal, which has an impact on the cost of bank debt.

The role(s) of public authorities in managing this market failure

Innovation is a key factor in growth and international competition. It is therefore in the interest of governments to implement measures that promote national innovation.

Higher education and research play a role in fundamental research and in training a workforce capable of innovation. In this way, the government is involved in the most fundamental stages of the creation of new technologies. However, the effects on innovation can only be felt if there are transfers from public research to the business world. This transfer can take two distinct forms, the first being the organization of research partnerships between public research laboratories and private companies. The second, less developed in France, is the transfer of knowledge through the creation of companies. Encouraging and facilitating the creation of companies by researchers enables technology transfer to start-ups which, if they succeed in developing innovation, will experience sufficient organic growth for the innovation to flourish in the business world. However, in France, this practice remains marginal because it is associated with too much risk in the event of failure.

The state can also create ecosystems conducive to the development of innovation by creating economic spaces where creators, professionals, and financiers can meet. In France, competitiveness clusters are designed to fulfill this role. In 2012, France had more than 7,000 companies that were members of 71 competitiveness clusters.[10]. These clusters organize research partnerships between public and private actors. They enable small entities to join forces with large companies, which thus gain access to the most innovative technologies.

The creation of an ecosystem conducive to the development of innovation and knowledge transfer is at the heart of the public mission. However, the state can also intervene directly in the financing of companies. This financing, which represents nearly 60% of external innovation funding, can take the form of direct loans to innovative companies or subsidies, paid in the form of tax credits or advances that are repayable only if the financed project is successful. In France, the primary public funding mechanism for research and development expenditure is the research tax credit, which frees up companies’ self-financing capacity by reducing their tax burden, subject to conditions on the use of the margins generated for innovation projects.

In 2011, 14,882 companies, 88% of which had fewer than 250 employees, benefited from €5.166 billion in CIR funding.[11]. Since 2008, this scheme has become the main source of public funding for companies’ research and development expenditure.

Finally, the government can also intervene in subsidies to financiers of innovative companies by adopting an advantageous tax policy and thus promoting the development of alternative financing tools that are more effective than financing innovative projects.

Alternative financing for innovation

Traditional financial intermediaries are unsuited to financing innovation. Their lack of technological monitoring and their sometimes divergent interests with the companies most prone to failure are not conducive to effectively financing innovation and guaranteeing the risk-taking essential to generating innovation. Acquiring a stake in the capital of innovative companies aligns the interests of the financier and the entrepreneur by maximizing the value of the company through the implementation of effective measures to achieve this. However, although controlling a significant share of a company’s capital allows for the alignment of interests, it cannot be separated from the technological expertise of the financiers in order to bring innovation projects to fruition.

Specialized venture capital and corporate venture capital[12]can therefore be effective in that the experience of the teams makes it possible to monitor technology and minimize the cost of incentives needed for the entrepreneur to make the optimal effort. In addition, this type of intermediation guarantees the viability of financing throughout the project, from seed to commercialization, as the profitability of a successful project increases throughout its life cycle.

However, these types of financing are subject to the financial capabilities of venture capital and corporate venture funds, the former being supported by business angels and private equity funds, the latter by the financing capabilities of large groups and their strategies.

France stands out from its European counterparts in terms of business angel behavior . With more than 4,000 investors, France appears to be the European country with the highest number of investors, along with the United Kingdom. However, one of the characteristics of these individual investors is that they invest a low average amount, estimated at €0.4 million by the European Commission[14], whereas it is over €1 million in most European countries, €2 million in the United Kingdom, and €7.1 million in Finland.

The government has therefore put in place mechanisms for pooling individuals’ financial resources, providing tax incentives for individuals to invest in mutual funds dedicated to financing innovation. These investment vehicles encourage the emergence of » subsidized » business angels , while allowing for higher average investments.

Recent measures in favor of corporate venture capital and crowdfunding demonstrate the importance of government intervention in the development and viability of alternative financing.

Conclusion

Access to financing for innovative projects in France has been guaranteed in particular thanks to state interventionism. However, France stands out for its strong propensity to intervene in favor of fundamental and applied research, and comparatively little in favor of other OECD countries.[15], in experimental development. This implies a preference for financing the least profitable phases of innovation.

According to the OECD’s Innovation Scoreboard, France appears well positioned in terms of resources, but mediocre in terms of results in terms of business investment and exports of knowledge-intensive services. Thus, the costs associated with indirect government funding through tax incentives for research and direct funding of domestic corporate research and development expenditure (DIRDE) amounted to 0.23% of GDP in 2007[16]. In order to contain government spending on innovation financing, the government will therefore have to focus on the more profitable phases of innovative projects. This could guarantee the viability of the French model and ultimately increase its performance.

Notes:

[1]The first publication of the Oslo Manual in 1992 by the OECD aimed to establish guidelines for the collection and use of innovation data.

[2]Financing Technological Innovation in Industry, November 2001

[3]Ratio of gross savings to gross fixed capital formation

[4]National accounts (Banque de France, INSEE), ECB

[5]In 2009, INSEE estimated that independent businesses accounted for 75% of the French economy, or 2.26 million companies.

[6]Christensen Clayton M, « The innovator’s dilemma: When new technologies cause great firms to fail, » Harvard Business Review Press, May 1997.

[7]Paris EUROPLACE report, « Financing businesses and the French economy: towards a return to sustainable growth, » 2013.

[8]See Augustin Landier, « Banks versus Venture Capital, » 2001

[9]Reference bank.

[10]Source: DGCIS – Annual survey of clusters, INSEE database

[11]Source: MESR-DGRI-SETTAR-C1 (Gecir, May 2013)

[12]Direct investment by large companies in the capital of innovative or technology-based SMEs

[13Individuals or self-employed persons investing directly in young companies, generally those with high technological potential.

[14]Indicators of access to finance – Business angels, European Commission

[15]See BEYLAT Jean-Luc, TAMBOURIN Pierre, PRUNIER Guillaume, SACHWALD Frédérique, « Innovation, a major challenge for France, » Ministry of Industrial Renewal, July 2013

[16OECD, Database of key science and technology indicators 2010

References

– « Report on Innovation: A Major Challenge for France, » Ministry of Productive Recovery, July 2013

– « The role of bank financing in the innovation process: The case of four European countries, » Hikmi A., Parnaudeau M, Vie & sciences de l’entreprise, 2008

– « The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail, » Harvard Business Review Press, May 1997

– « Report on the evolution of SMEs, » SME Observatory, BPIFrance, 2013

– « Innovation Union Scoreboard 2014, » OECD

– « Banks versus Venture Capital, » Augustin Landier, 2001