Industrial policy in France (2/2)

What is the rationale behind industrial policy?

Summary

– A distinction is made between vertical industrial policies and horizontal industrial policies.

– Industrial policies in France have been fundamentally reoriented as a result of European integration and are now part of the Community’s competition policy. The horizontal approach has been established.

– However, a vertical approach seems to be coming back into fashion, which raises the need to clarify industrial policy guidelines.

June 28, 1984 marked a little-known but nevertheless decisive turning point in French industrial policy. On that day, Creusot-Loire, a historic giant in the steel industry and a flagship of French industry, filed for bankruptcy with the Paris Commercial Court, which decided to put it into liquidation. Creusot-Loire had been hit hard by the first steel crisis in the 1970s, without being able to benefit from government support plans. Employing more than 30,000 people and posting losses of more than two billion francs in two years (just over €300 million), the state decided not to bail out the group, even though two years earlier it had agreed to take over some of its assets.

The decision by the state and the government not to bail out Creusot-Loire marked a fundamental break in the history of industrial policy in France, in that it signaled a major conceptual shift: public intervention was no longer about supporting a national champion, but was limited to implementing a retraining policy for the benefit of the employees and employment areas concerned. It thus lays the foundations for the distinction between vertical or sectoral industrial policies, which are based on a » state-strategist » approach, and horizontal industrial policies, which are designed to create conditions, economic environments, and regulatory frameworks favorable to industry. It symbolizes the abandonment of the former in favor of the latter.

This evolution was thought to have been definitively confirmed by European integration and the binding framework of competition policy established by the EU and rigorously enforced by the European Commission. Developments in the industrial economy were fully and resolutely in line with this European framework, arguing in favor of public action focused solely on correcting market imperfections in the allocation of resources in the productive sector. However, in recent years, vertical or sectoral industrial policy, more inspired by the » strategic state » paradigm, has been making a comeback in France. The change dates back to 2004, with the €3.2 billion bailout of Alstom, the world’s second-largest manufacturer of rail transport and shipbuilding.

This return to a » vertical » policy appeared to be confirmed and legitimized by the crisis industrial policy pursued between 2008 and 2012, which was also based on a sectoral approach (benefiting the sectors most affected by the crisis). Since then, however, the state seems to have alternated between a return to this vertical approach and the continuation of horizontal practices, as demonstrated by the recent creation of a public research center for the French steel industry as part of the « Florange dossier, » a method that is reminiscent of the » horizontal » choice to aid in restructuring made in 1984 with Creusot-Loire.

French industrial policy has thus been marked for several decades by a succession of sometimes contradictory conceptual shifts and reorientations. The state is hesitant about the strategy to adopt, but the decline of French industry makes conceptual clarification both necessary and urgent. While the legitimacy of industrial policy cannot be seriously contested, the vagueness surrounding its principles of action and modalities must be dispelled.

1. The basis of industrial policy: strategic imperatives and the correction of market imperfections

1.1 The strategic benefits of a strong industry

It is widely recognized that industry has a significant knock-on effect on the economy and that, in this sense, it is a key driver of growth. The 2005 Beffa report [1] estimated that, for every €1 of production, industry consumes €0.7 of intermediate consumption in France, compared with only €0.4 for services. As a lever for growth, a strong industry is also essential for a country’s successful integration into international trade and globalization. International trade remains largely composed of industrial goods, and it is still illusory to hope that the boom in service exports, even if it is significant, will rebalance our trade balance. If we look at EU exports to China, we see that 66% of them are industrial goods and only 22% are services.

This is where the real legitimacy of public intervention in industry lies: the strategic imperative. This is obvious in the fields of defense and energy, but also in transport and telecommunications. A principle of industrial sovereignty applies: there are strategic sectors that are crucial to the national interest at the heart of a country’s industrial activity, and these must sometimes be protected. In the field of national security, in particular, this translates into the state’s desire to prevent takeovers or excessive shareholdings in certain defense companies and industries. In this sense, its direct intervention in certain industries, such as the defense industry, is not open to debate, even if certain failures call for a thorough review of decision-making (the French industry, for example, completely missed out on the drone revolution, which the American military-industrial complex, on the other hand, was able to exploit).

1.2. Correcting market imperfections

This is the traditional justification for any public intervention in economic matters. Although there are few market imperfections specific to the industrial sector, certain markets present obvious barriers to entry due to the enormous scale of industrial investments. Developing production capacity often requires investments that are irreversible, or at least not in the short term ( sunk costs). As the risk incurred by private investors is too great, only public investors can offer sufficient capacity and guarantees to compensate for these shortcomings.

In the specific case of France, market imperfections are evident: as we have seen, the industrial and productive fabric is characterized by its bipolarity, polarized between high-tech companies and others with little technology, with a large part of French industry suffering from its mid-range positioning. The decline in competitiveness is ultimately only a symptom of this market imperfection.

1.3. Current industrial policy objectives

While it is unthinkable that the public authorities should seek to curb all the phenomena contributing to deindustrialization (productivity gains, outsourcing of services, changes in household consumption, growth in international trade), one economic policy option remains seriously credible: that of supporting innovation, thereby improving the competitiveness of industry, and working towards greater specialization of the productive fabric in the production of goods that are highly intensive in skilled labor and R&D.

In 2013, the main objective is to create the conditions for a return to competitiveness in French industry. To achieve this, the priority remains restoring corporate margins, which would enable a move upmarket, the main lever for remedying industrial decline.

2. The need to clarify industrial policy options

2.1. Dirigiste or vertical policies, which are sometimes necessary, have shown their limitations

The Economic Analysis Council (CAE) has identified three types of dirigiste or » vertical » industrial policies that are still in use today: » the mechanical-industrial state , » which acts directly on productive structures; « The stretcher-bearer state, » which provides assistance to sectors in difficulty—this is referred to as sectoral policy; and » The strategist state, » which directly supports sectors that are strategic for the country, through aid to major industrial projects and support for national or European » champions. »

A vertical industrial policy serves primarily to compensate for overly short time horizons, risk aversion, and market liquidity constraints. It is the state that can provide liquidity and act as a deep-pocketed investor with a longer time horizon and lower risk aversion than private agents. However, the limitation of such a practice lies in the significant risk of moral hazard: a large company, knowing that the state will inevitably come to its rescue, will be tempted to act at the risk of privatizing profits and nationalizing losses.

Another benefit of these policies has been, and still is, to keep human, physical, and technological capital within the country. Aid to struggling companies can be justified by this desire, as exits from markets are often irreversible and entries are difficult. They help to limit the effects of unemployment on a labor pool by preventing a bankruptcy from spreading to local suppliers and subcontractors. Nevertheless, there is a risk of providing non-repayable support to structurally unprofitable companies.

Such policies require the state, as a strategist, to be able to judiciously choose the right sector considered strategic for the future and, within that sector, the right national champion. However, while there has been much talk of « French industrial successes » such as nuclear power, the Concorde, the TGV, Airbus, Ariane, and Areva, several attempts have failed to deliver on their promises and have illustrated the flaws in the logic of the state as strategist: the cable plan, the satellite plan, and the machine tool plan of the 1980s swallowed up a volume of public subsidies equal to or even greater than the turnover of these sectors, without producing convincing results. One example is the Bull company in the 1980s and 1990s, where public aid amounted to €8 billion, and whose privatization ultimately brought in only €140 million to the state. Today, its residual stake is worth barely €10 million [2].

2.2. Industrial policies have been fundamentally reoriented to fit within a European framework

In recent decades, industrial policies have undergone a major overhaul in terms of their economic rationale, and their methods have been profoundly reoriented. Sector-specific and dirigiste policies designed to compensate for the supposed inability of markets to take long-term issues into account have been replaced by more horizontal industrial policy approaches. The objective of these policies is focused on improving the functioning of markets. Action is « horizontal » in the sense that it focuses on R&D, human capital, the overall functioning of markets, and the creation of favorable environments and contexts, rather than on specific sectors or individual companies.

It was European integration, through the competition policy that gradually became imposed on EU member states, that supported the reorientation of industrial policies in France. The state no longer acts on a sectoral basis or for the benefit of specific companies, as its scope for action is now constrained by EU competition rules, based on the European Commission’s control of state aid and crackdown on anti-competitive practices. Moreover, this competition policy is increasingly criticized for preventing the emergence of national or European » champions » by exercising overly strict control over mergers [3].

Within this European framework, industrial policy—integrated into the « Lisbon Strategy » and then into the EU 2020 project—has the clearly defined and constrained objective of stimulating the accumulation of human, physical, and material capital (i.e., research and development) in order to stimulate technical progress or productivity growth. In the European sense, industrial policy is therefore almost synonymous with innovation policy.

In a context of international competition, particularly with regard to the location of productive activities, the whole point of a » horizontal » approach to industrial policy is to work to enhance the industrial attractiveness of the territory to which it applies.

This logic is applied in practice through several instruments that are becoming increasingly important, foremost among which is the research tax credit (CIR). This reimbursement of 30% of R&D expenditure for an initial tranche of up to €100 million, and 5% above this amount, has helped to make France the world leader in public research funding and a small paradise for research and development. By reducing its cost and improving its profitability, the CIR plays a significant role in attracting companies’ R&D activities to France. Thirteen of the largest industrial groups generate 5% of their turnover in France, but maintain 50% of their R&D activities there.

Even though the research tax credit is a victim of its own success (the number of beneficiary companies doubled between 2007 and 2011 and has continued to increase since then), becoming increasingly costly for the state (currently €5 billion per year, almost €7 billion in the coming years), it remains the most generous public support tool for R&D in the entire OECD (0.26% of GDP). Although it is not without its flaws, both for the State (it is the largest tax loophole ever created in France) and for businesses (subject to ever-increasing tax audits and faced with the vagueness of the system’s boundaries, which has led to an explosion in the number of tax rulings and penalizes SMEs), its effect on France’s industrial attractiveness remains significant.

On the other hand, competitiveness clusters are the very symbol of these new industrial policies. Public authorities no longer intervene to determine priority sectors and products, as entrepreneurs are better able to respond effectively to market demands, but they do have a role to play in providing them with high-quality public structures and skilled human capital, and in promoting synergies between public and private research. Together with competitiveness clusters, they create incentives to bring together research, training, and production resources on the same site or in the same region. The model is openly based on that of California’s Silicon Valley. However, each local political authority tends to want its own competitiveness cluster, resulting in a scattering effect that tends to spoil the good idea, to the extent that there are too many competitiveness clusters in France (71 in 2013) and they are too small.

Finally, the 2012 Gallois report was part of this » horizontal » approach, in the sense that its recommendations address the productive fabric as a whole and not a particular sector. Among a whole series of measures (22 proposals) is the famous « competitiveness shock. » Despite its name, this » shock » is emblematic of the desire to remedy market imperfections and create an ecosystem favorable to industry, particularly in terms of taxation.

Louis Gallois’ competitiveness « shock » thus consisted of transferring €30 billion in social security contributions (representing 1.5% of GDP) to taxation and public spending cuts. Two-thirds of this transfer would have concerned employer contributions and one-third employee contributions.

For two decades in France, the main reductions in charges have affected low wages and have therefore had very little impact on industry, where remuneration levels are higher. In order to have a greater impact on industry and the associated high value-added services, this transfer of charges had to cover salaries up to 3.5 times the minimum wage, so that 35% of the benefit created by the reduction would go directly to industry.

Instead, the government opted to create a tax credit for competitiveness and employment (CICE) as part of a Pact for Growth, Competitiveness and Employment. This tax credit amounts to €20 billion, which is much less than the €30 billion in tax relief proposed by the Gallois report, even though this represented only half of the loss in corporate margins since 2001. In addition to its advantages and the progress represented by its very existence, the CICE also has two other drawbacks: firstly, it will only play its full role from 2014 onwards, while the number of industrial bankruptcies shows no sign of slowing down in 2013; secondly, it only supports salaries below 2.5 times the minimum wage, which will benefit service companies more than industry.

2.3. French industrial policy is still heavily influenced by « vertical » approaches, which are tending to return to the forefront

Nevertheless, several areas of contemporary industrial policy are still marked by the » vertical » approach inherited from the state as strategist. The Alstom affair in 2004 is particularly emblematic of this, when the French authorities decided to provide financial support to prevent the bankruptcy of Alstom, an industrial giant, a highly diversified technology conglomerate, and the world’ssecond-largest company in rail transport and shipbuilding. As a result of political determination, Alstom received €3.2 billion in aid, €800 million of which came directly from the state.

The » crisis industrial policy » pursued between 2008 and 2012 was seen as confirmation of the » Alstom logic » of 2004. The « crisis industrial policy » pursued between 2008 and 2012 was part of the same economic policy logic that had guided the management of the « Alstom » case in 2004.

In a context of widespread crisis, particularly in the industrial sector, with a decline in production and massive destocking in the automotive sector, the crisis industrial policy was based on a resolutely vertical and sectoral logic: support for the most affected sectors, with the introduction of a scrappage scheme in the automotive sector and a €6 billion loan to manufacturers and subcontractors, is the most emblematic symbol of this.

Numerous and overly scattered public structures

The creation of the Strategic Investment Fund (FSI) in 2008, a subsidiary of the Caisse des Dépôts et Consignations, is part of this sectoral and vertical approach, amplified by the » crisis industrial policy. » The purpose of this instrument is to provide » a response by the public authorities to the equity needs of companies that are drivers of growth and competitiveness for the French economy. » Since its creation, the FSI has acquired or recovered minority stakes in some 30 companies, mainly industrial ones.

The Agence des participations de l’État (State Shareholding Agency) continues to ensure state control of several strategically important industrial companies (EDF, SNCF, Areva) and manages significant holdings in a few others (Safran, GDF-Suez, Renault, etc.). However, it is regularly criticized for managing public holdings as assets rather than using them as a genuine industrial policy tool.

In line with this approach of creating powerful public players in the industrial sector, the Public Investment Bank, known as BPIFrance, was created in 2012. Its primary purpose is to bring together and streamline industrial policy instruments (merging Oséo, the SME bank, created in 2005 to facilitate access to financing for SMEs and which benefited from a large part of the funds from the major loan), CDC Entreprises, and the FSI. Similarly , a » National Industry Council » was established in 2013 .

Large-scale actions that are sometimes scattered

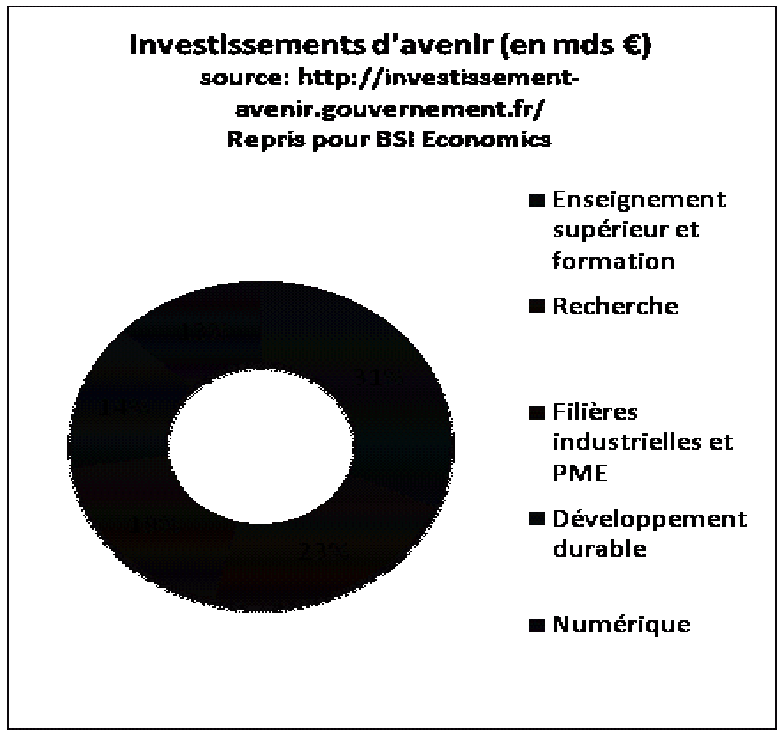

Future investments resulting from the 2008 major loan and the Rocard-Juppé commission also follow this » vertical » logic based on direct state funding of five strategic sectors, with a budget of €35 billion: higher education and training, research, industrial sectors and SMEs, sustainable development, and digital technology. Similarly, the 34 action plans presented to the Elysée Palace in September 2013 and mentioned above can be seen as emblematic of the strong comeback of this vertical approach: when the State sets three priorities (ecological and energy transition, the bioeconomy, new technologies) and when its ambition is to « guide, support and stimulate » investors, the approach appears to be significantly inspired by a vertical « State-strategist » logic.

Conclusion

A distinction must be made between deindustrialization, which is primarily the shift to a service economy, and industrial decline, which is a symptom of the erosion of the competitiveness of industrial companies.

Does this justify a return to a vertical approach to industrial policy? It could be argued that, in 2013, industrial policy consists primarily of giving both private and public companies the means to develop. Industrial activity is facilitated by a flexible and, above all, attractive regulatory and fiscal framework. In a country where industry now accounts for only 10 to 12% of national wealth, the priority remains attractiveness: attracting more foreign companies, which already employ almost 3.5 million French people in France, is perhaps one of the keys to overcoming industrial difficulties.

Bibliography

– Pierre-Noël GIRAUD and Thierry WEIL, L’industrie française décroche-t-elle ? (Is French industry falling behind?), La Documentation française, 2013.

– Augustin LANDIER, David THESMAR, 10 idées qui coulent la France(10 ideas that are sinking France), Flammarion, 2013.

– Patrick ARTUS, Marie-Paule VIRARD, France without its factories, Fayard, 2012.

– Louis GALLOIS, Pacte pour la compétitivité de l’industrie française(Pact for the Competitiveness of French Industry), Report to the Prime Minister, November 5, 2012.

Notes

[1] Jean-Louis BEFFA, Pour une nouvelle politique industrielle(Towards a new industrial policy), Report to the President of the Republic, 2005.

[2] Henri LAMOTTE, Applied Microeconomics, Labor Market and International Economy, Presses de Sciences Po, 2011.

[3] The Gallois report (November 5, 2012) was highly critical of European competition policy, which » dominates all other European policies, which can only be implemented within the framework it defines, » but which gives priority to consumers over producers: as a result, it fails to take into account the global competition in which companies operate. Decisions relating to competition (mergers, state aid) can only be challenged before the CJEU, and therefore according to criteria that are more legal than economic, and within procedural deadlines that are disconnected from industrial reality, according to Louis Gallois.