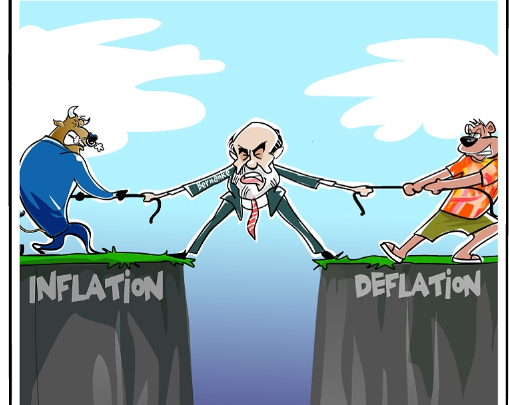

Real interest rates and the Fed: how to gain more room for maneuver in the event of a recession?

In a note from the Brookings Institute, Ben Bernanke, former chairman of the Fed, wonders how to significantly lower real interest rates in the event of another recession. Since real interest rates are the sum of nominal interest rates and inflation rates, there are two possible solutions.

The first is to lower the Fed’s key interest rate, with the risk of applying a negative rate. The second is to raise the inflation target from the current 2% to 4%. Ben Bernanke questions the implementation, costs, distributional effects, and political risks associated with negative interest rates and a higher inflation target.

A negative rate is simple to implement and has limited political risks. On the other hand, there are costs in terms of the profitability of banks, financial institutions, and mutual funds. Also, while a negative rate would not affect the deposits of the average saver, in order to maintain a long-term relationship, this would be less the case with investors. A higher inflation target would signal flexibility in the Fed’s mandate—since the target is permanent and not temporary like a negative rate—meaning less credibility for the institution, which would limit its ability to anchor inflation expectations and thus stabilize fluctuations in unemployment. In addition, bondholders would be affected by this new inflation target. Finally, Ben Bernanke insists on the need to discuss this inflation target, without ruling out negative rates as a potential complementary tool. More broadly, fiscal policy would be an equally, if not more, necessary complement to the role the Fed would have to play in the event of another recession.

Oil loses 8.5% over one month

How can we explain the 8.5% drop in the price of WTI oil over one month? Two factors may explain this.

First, monetary policy easing and fears of no rate hikes in the United States have pushed financial flows toward safe-haven assets, such as gold, and assets offering more attractive returns, such as emerging markets. Improved flows in emerging countries have eased their financial conditions, boosted their economic activity and ultimately supported base metal prices. The correlation between gold (attractive if there is no growth) and base metals (attractive if there is growth) has thus become positive. More surprisingly, the correlation between gold and the USD, which is usually negative, is no longer observed. Indeed, the market’s expectation of easing by the Bank of Japan has led to a depreciation of the yen against the dollar, while boosting the value of gold. The correlation between the yen and gold seems to have replaced that between the US dollar and gold.

The second factor is that the outlook for production supply has improved due to the latest announcements regarding Libya and Nigeria, leading to an upward revision of 500-700k in available supply in 2017. As a result, longer-term prices have been revised downwards, leading to a more negative carry trade on the oil price curve. At the same time, new short positions have entered the market, causing net contract positions to become negative, which reduces the attractiveness of oil relative to other commodities. As a result, oil is positively correlated with the depreciation of the yen and negatively correlated with industrial metals and gold. Asset allocation is adjusted downward for energy and upward for precious metals and base metals.