DISCLAIMER: The opinions expressed by the author are personal and do not reflect those of the institution that employs her.

Abstract :

- Environmental goods and services are necessary for the energy transition and help increase energy efficiency by offering cleaner production technologies and reducing all types of pollution (waste, noise, and ecosystem pollution).

- Local initiatives are multiplying to increase their production: countries or groups of countries are using incentive instruments, at the risk of competing with each other and limiting their effect on climate change.

- A trade agreement that helps facilitate access to environmental goods and services could complement national initiatives.

Environmental goods and services (EGS) are used to measure, prevent, limit, or correct environmental damage, such as pollution, as well as problems related to waste, noise, and ecosystem pollution (OECD/Eurostat, 1999).

This group of goods and services includes items as diverse as industrial filters, catalytic converters, and other emission scrubbers for air pollution; landfill sealing systems and household waste composting facilities for waste management; acoustic insulation shells and noise barriers that limit noise pollution, and high-efficiency electronic light bulbs and low-energy boilers that increase energy efficiency.

They are generally considered to be instruments that contribute to ecological transition. Accelerating this transition therefore depends in part on the production and accessibility of ESBs, which reduce the cost of environmental technologies, increase their use, and promote innovation and technology transfer (Balineau and De Melo, 2011).

Why is it necessary to reach an agreement to facilitate trade in ESBs?

First, it should be borne in mind that not all countries have the capacity or technology to produce these final goods and their components. For example, according to Garsous and Worack (2022), only a small number of companies, concentrated in a few countries, have the technological expertise to manufacture wind turbines. In this regard, barriers to trade in wind turbines prevent the dissemination of key environmental technologies to the greatest number of countries.

Furthermore (secondly), ESG production chains are by nature particularly fragmented (i.e., their production is spread across several countries). Increased trade in these goods would promote access to intermediate goods that are essential for the manufacture of final goods that reduce greenhouse gas emissions. To give a few examples, wind turbines contain around 9,000 components produced along global and regional value chains, electric cars are manufactured from components sourced from many countries, as are heat pumps. Reducing trade barriers would help support the growth of these markets (World Economic Forum, 2022).

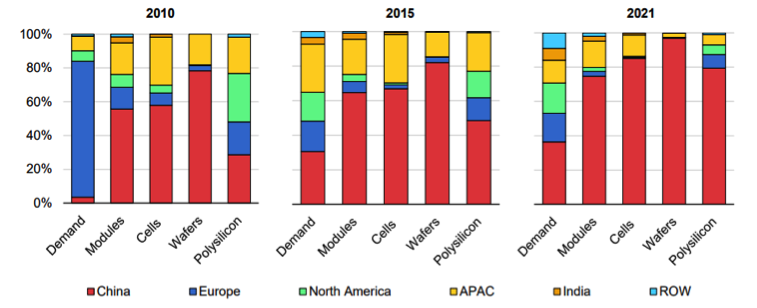

The technologies and production capacity for renewable energy-related goods are concentrated in a limited number of countries, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Production capacity of photovoltaic panel components by region, 2015-2021

Source: IEA, “Special report on solar PV global supply chain”

Finally, although tariffs on environmental goods are low on average, they remain significant in low-income countries. Representing up to 11% of their price, they are a major barrier to the acquisition of ESG. Development aid, and the customs duty exemptions it often enjoys, has become a key means of importing EGBs. The elimination of customs duties would thus help to level the playing field between certain goods financed by aid and goods imported through ordinary commercial transactions (OECD, 2005).

According to a WTO study that looks at the main ways that trade in environmental goods (EG) can affect CO2 emissions[5], the elimination of tariffs and non-tariff measures on the energy-efficient portion of these goods would reduce global CO2 emissions by 0.6% in 2030 compared to 2021 and increase global GDP by 0.8% based on projections through 2030. About half of this reduction in emissions would come from the removal of tariffs, while the other half could be attributed to the reduction of non-tariff barriers.

Where are we with the BSE liberalization agreements?

Efforts to classify these goods began in the 1990s, when the OECD’s Joint Working Party on Trade and Environment compiled a volume with an appendix containing an indicative list of environmental goods. This list was used as a starting point in the Doha Round negotiations under the auspices of the WTO, which, however, did not result in a greater reduction in customs duties for EGBs than for other goods.On July 8, 2014, a group of WTO Members relaunched plurilateral negotiations with a view to establishing the WTO Agreement on Environmental Goods (AEG) to promote trade in a number of key environmental products, such as wind turbines and solar panels. However, negotiations have been suspended since the18th round in November 2016. At that time, ministers and senior officials recognized that further work was needed and reiterated their shared commitment to concluding the EGA.

Individual initiatives on the use of ESBs?

In the absence of a multilateral agreement on ESBs, various countries are trying to accelerate the ecological transition by promoting local production and consumption of ESBs through protective trade measures. In the United States, for example, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), enacted on August 16, 2022, aims to strengthen energy security and ensure the ecological transition with the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40% from 2005 levels by 2030. The law provides for a total expenditure of $369 billion over 10 years, including tax credits for the purchase of « clean » vehicles and for improving the energy efficiency of homes, as well as tax and investment credits to increase U.S. production of solar panels, wind turbines, electric cars, batteries, and critical minerals.

Despite the important role these measures play in encouraging the use and production of these goods in the United States, they are accompanied by regulations that make tax credits and subsidies conditional on the origin of the components. For example, vehicles whose battery inputs come from « foreign entities of concern »(China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea) would ultimately be excluded from the benefits of the program. The IRA also imposes domestic content requirements or requirements based on the free trade agreement. (China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea) would ultimately be excluded from benefiting from the scheme[7]. The IRA also imposes requirements for domestic content or content originating from the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). By encouraging companies to establish or relocate their production to the United States[8], these provisions could create tensions with various US trading partners.

Similarly, the European Union (EU), through the NextGenerationEU project, plans to invest €18.9 billion in environmentally friendly technologies, develop greener vehicles and public transport, and make buildings and public spaces more energy efficient. The goal is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. The instruments differ from country to country. For example, with the €54 billion France 2030 investment plan over five years, France plans to provide significant subsidies to develop electric vehicle production on its territory and create a hydrogen sector. Although these instruments are beneficial locally for the development of green technologies and the production of environmental goods, multilateral cooperation, or trade liberalization following these individual initiatives by countries or groups of countries, would enable the dissemination of technologies that only certain countries have mastered and also make it possible to achieve a global environmental objective.

Indeed, this type of policy presents them with a dilemma: lose the opportunity to develop a local industry in favor of low-cost imports of ESBs, or gain autonomy by restricting trade and/or subsidizing domestic production. A first line of defense is to challenge them through WTO dispute settlement or similar mechanisms provided for in US free trade agreements. However, a longer-term strategy must be found, at the risk of seeing this type of policy multiply at the expense of countries least able to support their domestic production.

Conclusion

The environment is a global public good. Given the important role they have to play in accelerating the ecological transition, the dispersion of production, local solutions and initiatives are not enough to achieve a sustainable reduction in global emissions.

In particular, the accessibility of goods and technologies that reduce emissions is crucial for a rapid and widespread ecological transition: an agreement or instrument promoting cooperation is needed. Lowering tariffs, reducing non-tariff barriers, and standardizing the classification of ESBs[10] within a voluntary coalition of countries would be a beneficial way to preserve the accessibility of these goods to the largest number of countries while stimulating their global production.

References:

Bacchetta, M., Bekkers, E., Solleder, J., & Tresa, E. (2022). Environmental Goods Trade Liberalization: A Quantitative Modeling Study of Trade and Emission Effects.

Balineau, G., & de Melo, J. (2011). Stalemate at the negotiations on environmental goods and services at the Doha Round. FERDI Working Paper, 28.

Garsous, G., & Worack, S. (2022). Technological expertise as a driver of environmental technology diffusion through trade: Evidence from the wind turbine manufacturing industry. Energy Policy, 162, 112799.

Steenblik, R. (2005). Trade liberalization of renewable energy products and related goods: Charcoal, solar photovoltaic systems, wind turbines, and wind pumps.

World Economic Forum (2022). Accelerating Decarbonization through Trade in Climate Goods and Services. Insight Report.

World Trade Report (2022): Climate Change and International Trade, Geneva: WTO

[1]Water, air, and soil.

[2]Such as electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar panels, and heat pumps.

[4]A number of trade agreements include provisions to limit customs duties on certain BES, incidentally, as these are not specifically targeted.

[5]Bacchetta et al., (2022) take into account improvements in energy efficiency and the replacement of non-renewable energies with renewable energies.

[6]Exceptions are provided for in certain circumstances where domestic products are not available or are excessively expensive.

[7]A vehicle will therefore not be eligible for the tax credit as of January 1, 2024, if any part of the vehicle’s battery components has been manufactured or assembled by a covered entity, and as of December 1, 2025, if any part of the critical minerals contained in the vehicle’s battery has been mined, processed, or recycled by a covered entity.

[8]This is the case, for example, for Hyundai, the Korean company that now plans to locate its production in the United States by 2024. Hyundai Motor has indicated its intention to build a battery plant near the assembly plant, with the help of a partner, and Hyundai Mobis, an equipment manufacturer affiliated with the Hyundai Group (Financial Times).

[10] For example, more recently, the World Customs Organization (WCO) published the 2022 version of the Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System, which includes new commodity codes specific to several technologies using solar energy and energy-efficient light-emitting diodes. See also: Why new tariff codes are necessary to improve trade and combat climate change | LSE Business Review