Republishing of an article released in June 2020

Usefulness of the article: The effects of economic immigration on host countries are a hotly debated topic in the public sphere. This article summarizes the answers provided by economic literature and thus aims to refocus the discussion on key factors.

Summary :

· The labor markets of industrialized countries have an increasingly large share of migrant workers, even among the skilled workforce.

· Economic immigration creates winners and losers among native workers, both in terms of wages and employment, but on average the gains outweigh the losses.

·Skilled immigration can be a solution to labor shortages and helps to stimulate productivity and innovation in businesses.

· Policies to redistribute resources to domestic workers who lose out, better integration policies, and increased communication about the benefits of immigration could increase the level of acceptance among host populations.

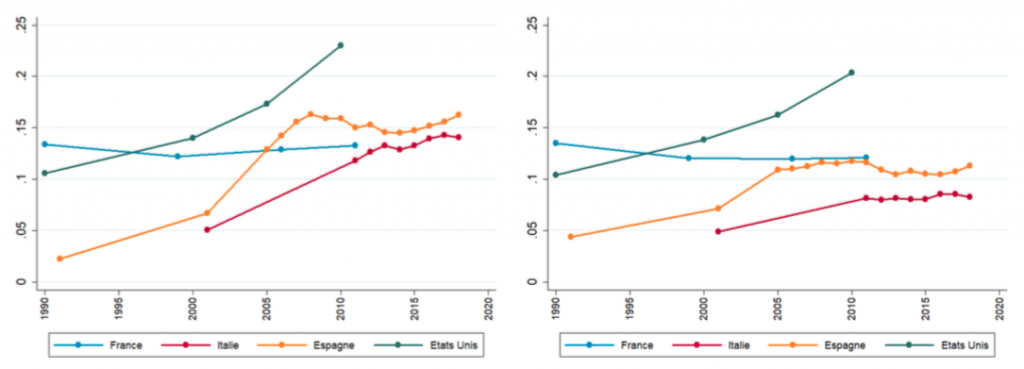

Theworkforcein many OECD countries includes an increasing number of migrant workers. Figure 1.a shows the evolution of the share of foreign workers between 1990 and today for France, Italy, Spain, and the United States. With the exception of France, where the share of immigrant workers was already high in 1990 but has not changed significantly since then, in the other countries considered, migrant workers occupy an increasingly important place in the workforce. This phenomenon may explain the current debates on the impact of economic immigration.

Figure 1: Change in the proportion of migrants among workers in four industrialized countries

a) Total workforce b )Highly skilledworkforce

Note: The reference population in panel a) includes individuals between the ages of 25 and 65 who are employed. Panel b) is limited to workers with a university degree. Series calculated from data provided by IMPUMS International.

Contrary to the commonly held belief that most migrant workers are low-skilled, Figure 1.b shows that the same upward trend is observed when the sample is restricted to workers with a university degree. This is partly explained by the fact that many industrialized countries have implemented policies aimed at attracting international talent. In the United States, for example, the H-1B visa system allows companies to sponsor the arrival of migrant workers with university degrees, while the United Kingdom and France offer a simplified visa application process for workers with rare skills that are in high demand by local companies.

Despite this, economic immigration, even when it mainly concerns skilled workers, is not unanimously welcomed by the population of host countries. Although immigration to the United Kingdom since the 2000s has increasingly consisted of graduate workers, this did not prevent widespread anti-migrant sentiment from being expressed during the Brexit vote. More recently, in the midst of the Covid-19 crisis, US President Donald Trump expressed his desire to significantly restrict the H-1B visa system, which sparked strong protests from industries that benefit from this system, such as the new technology sector.

This shows that the debate on the costs and benefits of labor immigration is far from over. In the following sections, I discuss the main responses provided by the economic literature.

1. Winners and losers

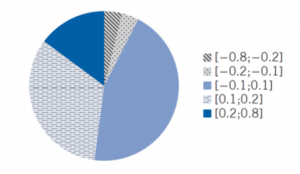

One of the most debated aspects of economic immigration is its effect on the wages and employment prospects of foreign workers. The answer depends greatly on the context and time frame of the analysis. Traditional models predict that domestic workers with skills similar to those of migrants are likely to see their wages decline in the short term, as they face increased competition that puts downward pressure on wages. Conversely, domestic workers with complementary skills are more likely to see their wages improve, as the arrival of migrants generates increased demand for their qualifications. These two effects tend to cancel each other out, so that the overall effect on wages is close to zero. Figure 2 shows that around 45% of the studies included in the meta-analysis by Peri (2014) find a very small overall effect, while the other half estimate that the overall effect on wages is positive.

Nevertheless, even in the short term, domestic workers with skills similar to those of migrants do not always lose out. On the one hand, migrants are often downgraded to jobs requiring lower qualifications than they possess and specialize in jobs that nationals tend to avoid because of atypical working hours or physical hardship (Dustmann, Frattini, and Preston, 2012). On the other hand, studies have shown that, following the arrival of a wave of migrants, nationals are pushed to specialize in activities where they have a comparative advantage, such as professions requiring language and communication skills, which can even lead to an improvement in their initial situation (Peri and Sparber, 2009; Foged and Peri, 2016). The population that seems to suffer most from a new influx of migrant workers are immigrants from previous waves, as they have the most similar characteristics and fewer opportunities to reinvent themselves.

Figure 2: Distribution of empirical results on the effect of immigration on wages

Note: this graph is taken from the note « Do immigrant workers depress the wages of native workers? »(Peri, 2014) and shows the results of a meta-analysis on the effects of migration shocks on wages. Just under half of the studies —shown in light blue in the diagram—find an effect close to zero(a 1% increase in the share of migrants leads to an effect of between -0.1% and 0.1% on wages),around 10% of the studies find a negative effect, and the remaining half find an overall positive effect.

In the longer term, companies adapt to the increase in the labor supply in the country by adjusting their capital stock in order to increase production levels, which brings wages back to their initial level. If the distribution of skills in the host country is permanently altered by immigration, there could be a change in the technologies favored by companies and in the distribution of the economy between sectors of activity. For example, Lewis (2011) shows that metropolitan areas in the United States that experienced a large influx of low-skilled migrants in the 1980s and 1990s invested less in automation, given the relative abundance of cheap labor.

Since the overall effect of immigration on wages appears to be zero (in the worst case) and positive (in the best case), one solution that is often proposed to make immigration more acceptable to domestic workers is to compensate those who lose out with transfers financed by the winners (Gagnon & Khoudour-Castéras, 2011). Since the overall effect is generally positive, these transfers would make all residents winners. Nevertheless, to our knowledge, no country has yet implemented policies directly aimed at this type of redistribution. This could be explained by the fact that it is more difficult to compensate the losers in the case of immigration than in the case of international trade or capital flows, as it would require the redistribution system to exclude new migrants from the beneficiaries (Felbermayr & Kohler, 2009).

2. A solution to labor shortages

Rapid technological change over the past 20 years has led to a boom in companies’ demand for technical skills, commonly referred to as STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). Since acquiring these skills requires many years of study, the supply of workers has been slow to adapt, leading to labor shortages.

Some countries, such as France and the United Kingdom, have adopted selective immigration policies to encourage the arrival of workers with these rare and highly sought-after skills. Furthermore, research by Raux (2019) shows that in the United States, companies that sponsor H-1B visas[1] generally do so because they have been unable to find a resident candidate who meets their criteria. In my recent work, I analyze the effects of these policies in France and find that immigration can be an effective tool in helping companies overcome skills shortages. Since, in these occupations, demand from employers exceeds the supply of labor available in the country, migrants do not reduce employment opportunities for nationals. Furthermore, alleviating shortages eases constraints on businesses by allowing them to grow more quickly, which in turn can create new job opportunities for other types of workers. The work of Beerli et al. (2020) shows that Swiss companies that reported suffering from skills shortages were the ones that benefited most from the introduction of free movement of workers with neighboring countries, in terms of growth, productivity, and innovation.

3. Immigration and Innovation

Finally, labor immigration can also fuel innovation. On the one hand, people who decide to migrate are, on average, more entrepreneurial than the rest of the population, given the difficulties and risks associated with international mobility.

On the other hand, as mentioned in the introduction, migrant workers in OECD countries are increasingly skilled, which is in itself a driver of productivity and innovation. Lincoln and Kerr (2010) show that the expansion of the H-1B visa program in the United States has led to an increase in the number of workers in science and engineering, which in turn has increased the number of patents filed by foreign-born inventors.

Finally, some analyses have questioned the role of diversity of origin as a driver of creativity, resulting from the confrontation between different ideas and points of view. The research has shown that there is a positive relationship between workforce diversity and business performance. However, this must be tempered by the negative effect of diversity on team cohesion and an increase in the costs associated with managing workers (Ozgen et al., 2013; Trax et al., 2015). The host country’s ability to successfully integrate migrants from different parts of the world is therefore crucial to minimizing the negative effects of labor immigration.

4. Conclusion

Economic immigration has an overall positive effect on the economies of host countries. It boosts wages and employment for domestic workers with complementary skills, who generally make up the majority of the workforce. In particular, the migration of highly skilled individuals can help companies address labor shortages in certain key occupations, enabling them to grow more quickly and potentially boosting productivity and innovation.

Opposition to migration flows is partly a rational response by workers who are most likely to suffer a loss of wages or employment opportunities, but it is also partly due to a lack of awareness of the benefits associated with economic immigration. A combination of policies promoting the redistribution of resources to negatively impacted workers, measures encouraging the successful integration of foreign populations into the host country, and better communication about the advantages associated with migration flows could increase acceptance of this phenomenon, which is far from coming to an end anytime soon.

References

Alesina, A., Harnoss, J., & Rapoport, H. (2016). Birthplace diversity and economic prosperity. Journal of Economic Growth, 21(2), 101-138.

Beerli, A., Ruffner, J., Siegenthaler, M., & Peri, G. (2018). The abolition of immigration restrictions and the performance of firms and workers: evidence from Switzerland (No. w25302). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Borjas, G. J. (2003). The labor demand curve is downward sloping: Reexamining the impact of immigration on the labor market. The quarterly journal of economics, 118(4), 1335-1374.

Card, D. (2001). Immigrant inflows, native outflows, and the local labor market impacts of higher immigration. Journal of Labor Economics, 19(1), 22-64.

D’Albis, H., Boubtane, E., & Coulibaly, D. (2019). Immigration and public finances in OECD countries. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 99, 116-151.

Doran, K., Gelber, A., & Isen, A. (2014). The effects of high-skilled immigration on firms: Evidence from h-1b visa lotteries. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Dustmann, C., Frattini, T., & Preston, I. P. (2013). The effect of immigration along the distribution of wages. Review of Economic Studies, 80(1), 145-173.

Dustmann, C., & Glitz, A. (2015). How do industries and firms respond to changes in local labor supply?. Journal of Labor Economics, 33(3), 711-750.

Dustmann, C., Schönberg, U., & Stuhler, J. (2016). The impact of immigration: Why do studies reach such different results?. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(4), 31-56.

Foged, M., & Peri, G. (2016). Immigrants’ effect on native workers: New analysis on longitudinal data. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 8(2), 1-34.

Ghosh, A., Mayda, A. M., & Ortega, F. (2014). The impact of skilled foreign workers on firms: an investigation of publicly traded US firms.

Kerr, S. P., Kerr, W. R., & Lincoln, W. F. (2015). Skilled immigration and the employment structures of US firms. Journal of Labor Economics, 33(S1), S147-S186.

Kerr, W. R., & Lincoln, W. F. (2010). The supply side of innovation: H-1B visa reforms and US ethnic invention. Journal of Labor Economics, 28(3), 473-508.

Lewis, E. (2011). Immigration, skill mix, and capital skill complementarity. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(2), 1029-1069.

Mayda, A. M., Ortega, F., Peri, G., Shih, K., & Sparber, C. (2018). The effect of the H-1B quota on the employment and selection of foreign-born labor. European Economic Review, 108, 105-128.

Moreno-Galbis, E., & Tritah, A. (2016). The effects of immigration in frictional labor markets: Theory and empirical evidence from EU countries. European Economic Review, 84, 76-98.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2019). How do OECD countries compare in their attractiveness for talented migrants?.

Ottaviano, G. I., & Peri, G. (2012). Rethinking the effect of immigration on wages. Journal of the European Economic Association, 10(1), 152-197.

Ozgen, C., Nijkamp, P., & Poot, J. (2013). Measuring cultural diversity and its impact on innovation: longitudinal evidence from Dutch firms.

Parrotta, P., Pozzoli, D., & Pytlikova, M. (2010). Does labor diversity affect firm productivity. Aarhus School of Business Working Paper, (10-12).

Paserman, M. D. (2013). Do high-skill immigrants raise productivity? Evidence from Israeli manufacturing firms, 1990-1999. IZA Journal of Migration, 2(1), 6.

Peri, G. (2012). The effect of immigration on productivity: Evidence from US states. Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(1), 348-358.

Peri, G. (2014). Do immigrant workers depress the wages of native workers?. IZA world of Labor.

Peri, G. (2016). Immigrants, productivity, and labor markets. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(4), 3-30.

Peri, G., Shih, K., & Sparber, C. (2015). STEM workers, H-1B visas, and productivity in US cities. Journal of Labor Economics, 33(S1), S225-S255.

Peri, G., & Sparber, C. (2009). Task specialization, immigration, and wages. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(3), 135-69.

Raux, M. (2019). Looking for the « Best and Brightest »: Hiring difficulties and high-skilled foreign workers. AMSE Working Paper.

Signorelli, S. (2019). Do Skilled Migrants Compete with Native Workers? Analysis of a Selective Immigration Policy. PSE Working Paper.

Trax, M., Brunow, S., & Suedekum, J. (2015). Cultural diversity and plant-level productivity. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 53, 85-96.

[1] The H-1B visa is a US work visa that allows holders to obtain a work permit in the United States. It accounts for the majority of work visas granted by US immigration services and mainly concerns skilled workers such as engineers and IT specialists.