Abstract:

– Although France has an energy heritage that remains highly valuable, it is time to rethink its energy model in the face of a changing world.

– A draft law on energy transition was adopted in October 2014 and aims to set targets for the transition to sober, innovative, and low-carbon economic growth.

– The success of the energy transition will depend heavily on effective cooperation and rapid, active, and proactive responses at all levels.

The beginning of the 21st century has been marked not only by a deep economic crisis but also by an exceptional new energy crisis. The traditional complexity created by the tension between fossil fuel prices in a context of strong growth in global energy consumption and uncertainty in energy policies is now compounded by the threats of climate change. The latter is caused by greenhouse gas emissions resulting from the consumption of polluting and non-renewable energies (oil, gas, and coal) for over a century. If we continue at the current rate, with around 2 billion new arrivals over the next 35 years, the future of energy will be too vulnerable to the risks of energy supply shortages and environmental disaster (Chevalier and Geoffron, 2012). All these factors require profound changes to be made to the current energy system over the next two decades.

Energy transition – a global challenge

All countries, with different policies and different levels of commitment, have responded to these new energy challenges. In Europe, the Climate and Energy Policy, defined by the European Union in 2009, is known as the « 3×20. » The aim is to increase the share of renewable energies to 20% by 2020, reduce CO2 emissions by 20% compared to 1990 levels, and increase energy efficiency by 20%. In Germany, for example, the government adopted an energy transition law (Energiwende in German) in 2010, which has two objectives: to reduce emissions through an energy mix that is more focused on renewable energies and to phase out nuclear power – a commitment that has been in place since the early 2000s. In the early 2000s, the United Kingdom became fully aware of the consequences of global warming (British economist Nicholas Stern was one of the first to quantify its economic impact in his 2006 report[1]). In Japan, following the Fukushima nuclear disaster in March 2011, the country also decided to phase out nuclear power by the end of the 2030s. Japanese manufacturers are at the forefront of developing new environmentally friendly technologies such as hybrid and electric cars. More recently, the United States, which refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol, and China—the two biggest polluters on the planet—have reached an unprecedented agreement on commitments to combat global warming[2].

France, albeit a little behind its British and German neighbors, launched a major national debate on « energy transition » in September 2012. This political decision resulted in a bill on energy transition for green growth, which was adopted by the National Assembly on October 14, 2014, at first reading. Nevertheless, implementation remains too slow and, in particular, awareness of this issue among the French population is still largely insufficient. This is the result of the unparalleled advantage of the French energy system, which is independent of fossil fuels and has the lowest electricity prices in Europe, which has now become a very strong « illusion » among the population about the inertia and rigidity of such a system in the long term.

In France: Is it time to wake up from the energy fairy tale?

The French energy model was ranked third in the world for its performance (after Norway and Sweden) at the World Economic Forum in 2013.

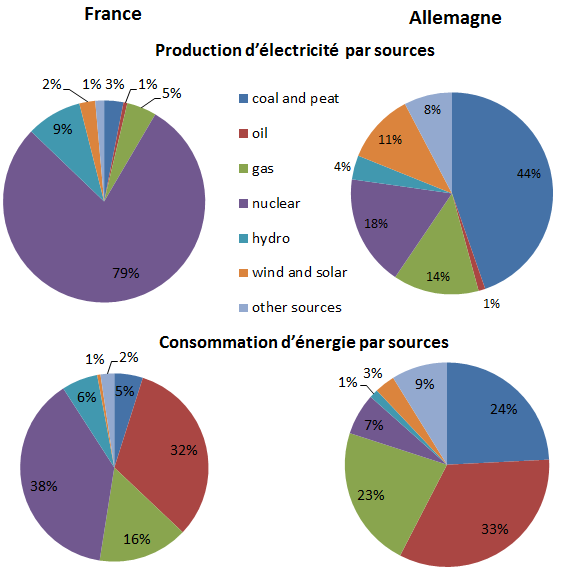

Figure 1. Energy and electricity balance in France and Germany

Source: BP, IEA (2013), BSI Economics

In Europe, France is among the countries with the lowest electricity prices: French households pay on average 30% less for their electricity bills than European households and 50% less than German households, according to Eurostat data from 2010. In addition, the French electricity system has an exceptional advantage thanks to its nuclear-based electricity balance (Figure 1): 80% of the electricity produced in France comes from nuclear power plants. France therefore benefits from some of the cheapest and least carbon-intensive electricity in the world. As for gas and oil, which account for 50% of France’s energy balance (Figure 1), it seems that the French are never short of supplies, even in times of great tension such as the gas crises between Russia and Ukraine, thanks to a good balance of supplies (Chevalier, Cruciani, and Geoffron, 2013).

However, it is time to rethink the energy system because, despite this performance, France, along with other interconnected European countries, is entering a new period where uncertainty reigns on all sides, where the advantages of the past model are being called into question, and where greenhouse gases know no borders.

– Electricity prices for households (tariffs) in France are indeed lower than most European prices. However, it should be noted that they have not changed since 1994 in nominal terms, despite fuel price pressures (the price of oil, for example, rose from $20/barrel in 1999 to around $140 in 2008 and around $100 in recent years). In other words, they are artificially low because politicians on both the left and right have done everything they can to block prices, regardless of costs, the market, and financing needs. This was demonstrated in the IFRI report on the evolution of electricity prices for domestic customers in Europe in 2011 and in the 2012 report by the Court of Auditors on the costs of the nuclear power industry. In France, costs have not been fully passed on to consumers. Electricity tariffs do not reflect market reality but increasingly reflect a desire to protect consumers from the tensions of the energy world. The French pricing system is therefore far from being a consistent and interpretable signal for manufacturers and consumers to make their investment or consumption choices, further delaying progress in the energy transition.

– Today, the advantages of nuclear power are being called into question, particularly in the wake of the Fukushima accident in March 2011 in Japan. Several factors affecting the cost of nuclear power have been reassessed or added due to stricter safety standards, including decommissioning costs, spent fuel management costs, long-term waste management costs, etc. (as demonstrated by several difficulties encountered in the development of the new Flamanville reactor). As a result, the cost of producing nuclear electricity will increase in the short to medium term, not to mention the risks associated with radioactive content, possible contamination, and waste storage. This deserves to be one of the major issues in the national debate on future investment choices.

– The future of energy has never been so uncertain. Oil prices—which drive the entire energy sector and remained very low throughout the 1990s—havequadrupled since 2000 and are still on the rise due to supply tensions, political turmoil in producing countries, and a possible increase in taxes on consumption.[3]… (Chevalier, Derdevet, and Geoffron, 2012). Furthermore, almost all of the energy used in France (including uranium) is imported from countries classified as « high risk. » This heavy dependence on primary energy imports poses a problem for long-term security of supply, even if the choice of nuclear power has mitigated the risks.

– Global warming is not confined within national borders. In France, even though a large proportion of electricity consumption is covered by nuclear power plants, thermal power plants (gas and coal) – which emit greenhouse gases – are needed to meet « peak » demand. Furthermore, greenhouse gas emissions are not limited to electricity production. Gas, coal, and oil consumption accounts for almost 53% of France’s energy balance. In the face of global warming, all countries, including France, must take responsibility for combating this threat.

It is in this context that the national debate on the « energy transition » was launched by the President of the Republic in 2012, resulting in a bill passed by the National Assembly in October 2014.

Energy transition: specifications

The draft law on energy transition consists of 60 articles that aim to » set objectives, outline the framework, and put in place the tools necessary for all the nation’s driving forces—citizens, businesses, territories, public authorities—to build a new French energy model that is more diversified, more balanced, more secure, and more participatory… », the main points of which are summarized below:

Transition to a low-carbon, energy-efficient economy

– Reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 40% between 1990 and 2030.

– Halve energy consumption by 2050

– Diversify technologies and models in the energy structure: Reduce fossil fuel consumption by 30% and increase the share of renewable energies to 32% of gross final energy consumption by 2030; reduce the share of nuclear power in electricity production from 75% to 50% by 2025.

Transition to an innovative and smart economy

– Thermal renovation of 500,000 homes per year, particularly with a view to reducing the energy insecurity of households faced with increasingly heavy bills (and due to rising unemployment).

– Develop clean transportation to improve air quality and protect the health of French citizens (bonuses for the purchase of electric vehicles and for the installation of charging stations for electric cars by individuals, 7 million charging points for electric cars by 2030).

– Mobilize new intelligence in the energy system: smart grids, smart buildings, smart cities, smart consumers, etc.

These objectives are very ambitious but achievable: « ambitious » because the energy future we are building is based on a scenario of very low growth in energy demand. The transition from 75% to 50% nuclear power would mean that an equivalent substitute of 88.5 TWh would have to be found in ten years. This share, plus the reduction in the share of coal and gas, would have to be replaced by renewable energies (mainly solar and wind power[4]), which are very costly to implement on a large scale due to their intermittency and unpredictability (Germany can be cited as an example – See also). « Achievable » because it is possible to draw inspiration from the energy transition of neighboring countries that were pioneers in this field. Indeed, much progress has been made in recent years: Smart Grids with decentralized electricity networks and demand response mechanisms are being implemented; large-scale electricity storage, although costly, is also progressing;CO2 processing to make fossil fuels clean is possible at a certain cost; many homes are being built with a series of energy efficiency criteria; electricity generated by offshore wind turbines has a large capacity and a significant reduction effect on wholesale electricity prices. In any case, we are still at the very beginning of a very long and difficult process. Implementing this project will be a major challenge and will depend heavily on rapid, active, and proactive responses at all levels.

Energy transition: It’s time to react at all levels

We are now in an interconnected energy system—that is, « linked with our neighbors by energy networks »: electricity generated by a power plant in northern France could travel a long way through transmission lines in Germany before reaching southern France, cubic meters of gas imported from Norway pass partly through the Netherlands and Belgium to be ultimately consumed in France, etc. Energy production and consumption patterns generate externalities that transcend simple national borders. Many of the decisions taken in France are no longer made solely in Paris. For all these reasons, the success of the French energy transition requires solid and effective cooperation between Member States.

This is to ensure that the energy transition, with its long list of ambitious goals, does not become a fairy tale designed to ease tensions in Brussels or appease the population with promises of job creation.[5], it is essential that politicians (at the national, regional, and local levels) and economists reach a consensus. Over the past few decades, energy policy in France has been dominated by the pursuit of economic rationality… intertwined with political considerations[6]leading, in particular, to electricity pricing policies that are incomprehensible (See also). In the coming years, it will be necessary to end the system of politically blocked tariffs and ensure that the pricing system sends a consistent and interpretable signal to consumers.

Beyond all these government commitments, the energy transition would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to achieve without the willingness and cooperation of citizens. From this perspective, it is worth noting that in our neighboring country, there is a broad consensus among the German population that phasing out nuclear power is essential. The day after the Fukushima disaster, the German government decided to immediately shut down the eight oldest nuclear power plants, even though this would lead to higher electricity prices, as expensive fossil fuels would have to be used during the transition period. This decision was supported by almost all German citizens. The transition to renewables, which led to high prices due to subsidies for this type of energy, also received (at least initially) strong support from the population in this country.

In France, it is necessary to accept that the era of cheap and abundant energy is over and that investing in a renewable and innovative economy comes at a cost. Citizens, consumers, and businesses are all now affected to some degree by the implementation of the energy transition for green and sustainable growth.

Conclusion

Recent years have been marked by a global awareness of energy issues. Although France has an energy heritage that remains highly valuable, its energy model is on high alert in the face of a changing world.Inaction is no longer an acceptable policy. It is in this context that a draft law on energy transition was adopted in October 2014, which aims to set targets for the transition to sober, innovative, and low-carbon economic growth. In a nutshell, the aim is to reduce the share of nuclear and fossil fuels, which would be replaced by a larger share of renewable energies, and to halve energy consumption by 2050 through an energy efficiency campaign. Thisambitious political decision is a step in the right direction. The success of the energy transition will depend heavily on effective cooperation and rapid, active, and proactive responses at all levels.

[2] The United States has announced a 26-28% reduction in its emissions by 2025 compared to 2005, and China, the world’s largest emitter, is expected to reach peak greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 at the latest.

[3] The domestic consumption tax on energy products (TICPE) is the main tax levied on petroleum products. It specifies that only uses as fuel or heating fuel are taxed.

[4] Hydropower, although a renewable energy source, has almost reached its maximum potential. Potential projects are systematically contested due to their conflict with other uses of water or their impact on the environment (biological continuity, sediment transport, etc.).

[5] The energy transition is estimated to create 15,000 jobs in France in the coming years.

[6] One example is the government’s decision to pass a law banning the exploration and exploitation of shale gas without even assessing the economic aspects: how much is available, at what cost, and what the consequences for the environment and the economic impact on businesses and regions might be.

Reference

Chevalier, J.-M.; Derdevet, M. and Geoffron, P., « L’avenir énergétique : cartes sur table » (The future of energy: cards on the table), Editions Gallimard, 2012.

Chevalier, J.-M. and Geoffron, P., « Les nouveaux défis de l’énergie: Climat – Economie – Géopolitique » (The new challenges of energy: Climate – Economy – Geopolitics), Economica, 2011.

Chevalier, J.-M.; Cruciani, M. and Geoffron, P., « Energy transition: The real choices, » Odile Jacob, 2013.

Court of Auditors, « The costs of the nuclear power industry, » January 2012.

Cruciani, M. « Evolution of electricity prices for domestic customers in Western Europe, » Ifri Note, November 2011.

Stern, N., « The Economics of Climate Change, » 2006.