Summary:

– In France, there has been a juxtaposition of different types of prices and tariffs, as well as a wide divergence between these prices in the wholesale electricity market in recent years.

– Government efforts to reconcile the contradictions between economic, social, and political objectives have led to even more contradictions in the electricity market.

– The price on the wholesale electricity market in France is therefore far from being a good signal for new investment and also far from being competitive as expected by the NOME law.

Over the past 30 years, the organization of the electricity sector has undergone political changes that have fundamentally restructured the industry: market liberalization and deregulation. Under the influence of a combination of economic, political, and technological forces, this industry is increasingly less controlled by governments. Certain segments of the value chain (particularly the production sector) are open to competition under various terms and conditions.

In France, after a long period of resistance to the wave of liberalization in the European market, the French electricity sector finally opened up to competition in 2000. Wholesale electricity prices[1]were determined solely by market forces. However, if we look at the wholesale pricing system on the French electricity market, we find, on the one hand, an overlap of different types of prices and tariffs, which vary widely from one price and tariff to another. On the other hand, since the liberalization of the electricity market, there has been an extraordinary rise in market prices: the long-term market price index (Powernext Baseload Forward Year Ahead) more than tripled between 2003 and 2008, rising even faster than oil (Figure 1 below). This has led to doubts and discontent about competition in the French electricity market.

The divergence between the regulated tariff and the market price on the French wholesale market

With the opening of the market in 2000, a number of eligible consumers decided to leave the regulated tariff system to participate in the market price system, which at that time was relatively low. However, this choice was irreversible.

Since 2005, the market price has begun to rise well above regulated tariffs. It tripled between 2004 and 2008, rising from €24 to €87/MWh, while regulated tariffs remained virtually unchanged at around €30/MWh. Regulated tariffs have remained largely fixed on the basis of the cost of producing nuclear and hydroelectric power, which accounts for 90% of total production in France. They have therefore been little affected by the increase in fossil fuel prices or the integration of CO2 prices since 2005.

Market prices, however, respond to all these changes. This is because market prices have aligned with the costs of the most expensive means of production needed to cover 100% of demand. Thus, even if a gas or coal-fired power plant is needed to cover less than 10% of production at any given time, the cost of these plants constitutes the reference price for the market. They are called marginal power plants—that is, the last power plants mobilized to meet demand.[2]. The cost per MWh of the fuel consumed in these plants – the marginal cost – therefore sets the market price. On the other hand, if the French electricity system were isolated, i.e., with no exchanges with neighboring networks, nuclear power plants would be the marginal power plants in nearly 50% of cases, and market prices would generally be set according to the marginal cost of nuclear energy; the gap between the regulated tariff and market prices would thus be narrowed.

However, with the opening of the market and the interconnection between France and neighboring countries, the marginal power plants needed to meet demand in the interconnected zone are mostly coal or gas-fired.[3]. Market prices align with the cost of these plants, which in turn varies with the volatility of fossil fuel prices. Figure 1 below also illustrates the correlation between electricity market prices and crude oil prices—the leading price in the energy sphere.

Figure 1. The coexistence of market price and tariff systems in the wholesale electricity market in France.

Source: Author, based on data from EPEX, CRE, U.S.EIA, Eurostat, BSI Economics.

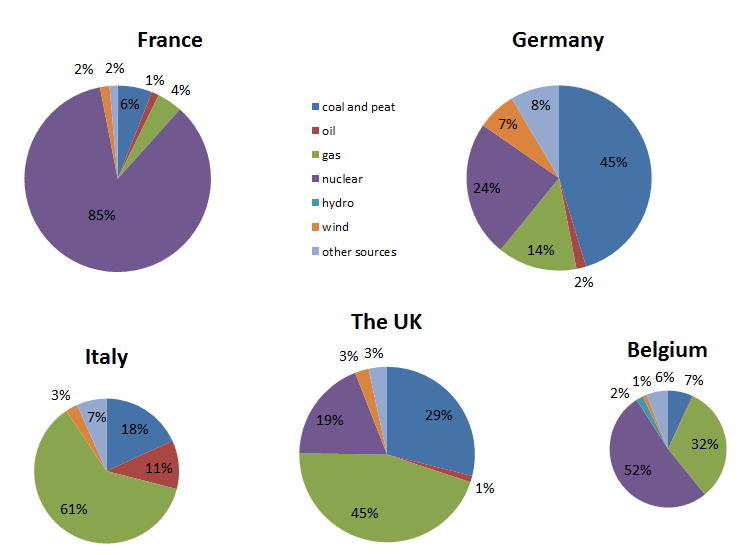

The increase in crude oil prices since 2004 has led to increases in the prices of two other fossil fuels: coal and gas, and has therefore had an impact on electricity market prices. As explained above, even though coal- and gas-fired power plants account for a very small share of total production in France, the cost of production at these plants will still be the benchmark price for the market, as it is linked to other markets such as Germany, where half of electricity production comes from coal and gas. Figure 2 below shows the diversity of electricity balances between France and its neighboring countries.

Figure 2. The diversity of European electricity balances

Source: Author, based on data from IEA, BSI Economics

During periods of peak demand, electricity is imported from neighboring countries; prices are aligned with the relatively expensive gas-fired power plant. Conversely, outside of peak consumption periods, electricity is exported to these countries. Even if prices correspond to a certain marginality of nuclear power plants in France, coal and gas-fired power plants that operate almost all the time in Germany or Italy could influence French electricity prices (Champsaur, 2009).

The juxtaposition of different types of prices and tariffs in the wholesale market

The divergence between the regulated tariff and the market price, as well as the extraordinary rise in prices since 2005, have led to dissatisfaction among consumers who have left the regulated system with regard to liberalization (in general, competition would have led to lower prices). This contradiction led the French government to adopt an energy law in 2006 that allows consumers who have left the regulated tariffs to return to the protected tariff system, known as « Transitional Regulated Market Adjustment Tariffs » (TaRTAM), or, more prosaically, « return tariffs. » The TaRTAM, calculated on the basis of the regulated tariff, increased by 10%, 20%, or 23% corresponding to an ex-post compensation mechanism.

The juxtaposition of regulated tariffs, TaRTAM, and market prices, as well as the conditions of irreversibility between regulated and market offers, have caused even more contradictions. Two customers with the same consumption profile do not have access to the same tariff offers. As pricing is inconsistent, market prices cannot be a signal for new investments. Furthermore, new entrants had no incentive to enter the market at the current regulated tariffs, which reflect the cost of the incumbent operator’s nuclear fleet, to which its competitors do not have access. If prices had been maintained as they were, there would have been no economic incentives for new entrants. This raises a new contradiction: competition is generally supposed to lower prices, but in order to promote competition in the French electricity market, we need to raise prices!

It was under these conditions that, in December 2010, the law on the New Organization of the Electricity Market (known as the « NOME » law) was enacted. The purpose of this law is to strengthen competition by gradually eliminating regulated tariffs and TaRTAM. In addition, under this law, EDF is required to sell part of its nuclear production to its competitors at a regulated price set by the regulator—the Regulated Access to Historic Nuclear Electricity (ARENH) system. The ARENH price requested by EDF’s competitors was €35/MWh, while EDF proposed €42. It was finally set by the government at €40/MWh from July 1, 2011, to be consistent with TaRTAM, then €42/MWh from January 1, 2012.[4]. Some of EDF’s competitors claimed that at such a price, there was insufficient economic scope to stimulate competition and that alternative suppliers had effectively become EDF’s « marketers. » As a result, alternative operators are not considered credible competitors and new entrants have no room for development.

The NOME law does not necessarily encourage alternative operators to participate in French nuclear energy production, as mentioned in the Champsaur report. There is no immediate advantage for alternative operators to invest in nuclear production. For this reason, the NOME law is even described as a « sad law » (Chevalier et al. 2012).

Conclusion

The government’s efforts to reconcile the contradictions between economic, social, and political objectives in recent years have led to even more contradictions in the electricity market. A number of laws and regulations have expired and a number of others have been replaced, creating great uncertainty about future electricity prices in France. This would have an immediate impact on the long-term outlook for consumers, alternative operators, and new entrants in particular. The price on the wholesale electricity market in France is therefore far from being a good signal for new investment and also far from being as competitive as expected by the NOME law.

« The gap is widening between politically blocked tariffs and a market reality that will inevitably prove painful in the years to come: electricity prices in France are lower than the European average, but this gap reflects less and less an advantage resulting from wise choices made in the past, and more and more a desire to protect consumers from the tensions of the energy world, further delaying progress in the energy transition » ( Chevalier et al. 2012, p. 97).

Notes:

[1] The wholesale market refers to the market where electricity is traded (bought and sold) before being delivered to the grid for end customers (individuals or businesses).

[2] In an electricity grid, supply is matched to demand in « order of merit »: at any given moment, the power plants that are least expensive in terms of fuel per MWh produced (such as hydroelectric and nuclear power plants) are used first, followed by more expensive power plants (such as coal or gas-fired power plants) until supply finally meets demand. Nuclear power plants will therefore operate most of the time, while coal- or gas-fired power plants are only used for a limited number of hours (during periods of peak demand).

[3] In France, electricity production is dominated by nuclear power, while at the European level, the structure of the production fleet varies greatly from one country to another. For example, in Italy, which has no nuclear power, electricity production relies mainly on coal, natural gas, and petroleum products.

[4] The ARENH price is, prosaically, a regulated wholesale price. It is higher than the hypothetical level proposed by the Champsaur report, as it takes into account the Fukushima disaster at the end of 2011 (many costs were added to ensure the safety of the nuclear energy system).

References:

– Chevalier. J-M, Derdevert. M, Geoffron.P ( 2012), L’avenir énergétique : cartes sur table(The future of energy: cards on the table), Folio.

– Ministry of Ecology, Sustainable Development, and Energy(2009) Report of the commission on the organization of the electricity market, chaired by Paul Champsaur, April 2009.

– Ministry of Ecology, Sustainable Development and Energy(2011) Report of the commission on the price of regulated access to historic nuclear electricity (ARENH), chaired by Paul Champsaur, March 2011.