Summary:

– Germany plans to carry out an ambitious energy transition, known as Energiewende, by phasing out nuclear power by 2022 and relying more heavily on renewable energies.

– However, this energy transition is likely to be accompanied initially by higher consumption of fossil fuels and increased energy dependence on imported gas.

– The challenge for Germany is to develop new technologies to « store » renewable energy, despite physical and climatic constraints.

– The total cost ofthe Energiewende couldexceed €2 trillion, not to mention the fact that the phase-out of nuclear power is likely to increase electricity bills for businesses and households.

One of the side effects of the Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan in 2011 has been a change in Germany’s approach to energy. The country has embarked on an energy transition process that includes phasing out nuclear power by 2022. One of the consequences of this transition process is the shift from electricity production based on fossil fuels to production based on renewable energies. While the population currently supports this policy, the foreseeable rise in energy prices and the resulting costs could change the situation, as households and businesses will bear the brunt of these increased costs. Numerous constraints and difficulties are bound to arise.

A unique situation, ambitious goals, and practical questions

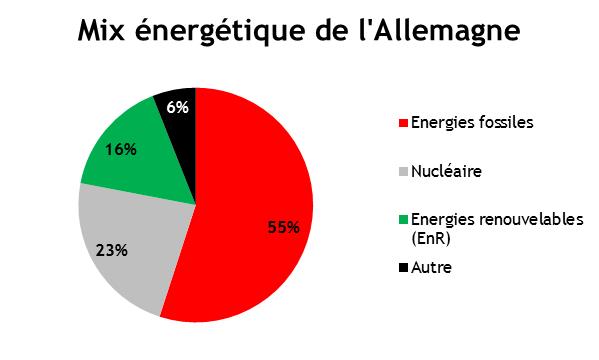

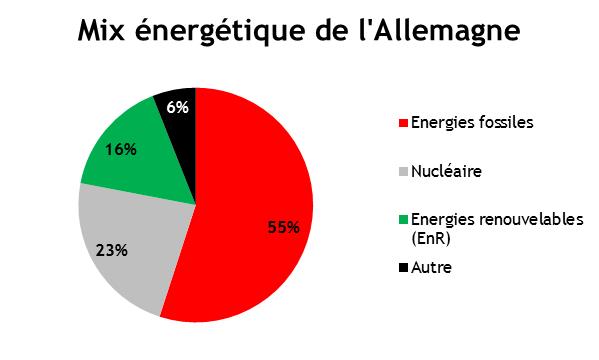

Germany is the most densely populated country in Europe and the country in which industry accounts for the largest share of the national economy. The German energy mix, in other words the distribution of the various primary energy sources consumed, is largely dominated by fossil fuels (oil, gas, and coal), which are major emitters of greenhouse gases (GHG). One of the results of this energy mix is that, on average, a German emits 9 tons of carbon dioxide (CO²) per year, compared to 5.8 tons for a French person. Nuclear energy is the country’s second largest source of energy, accounting for 23% of consumption, with the rest coming mainly from renewable energies (RE).

After the nuclear accident in Fukushima, Japan, in 2011, Germany set itself several ambitious energy transition targets: developing RE, reducing energy demand, and cutting GHG emissions. The country, where renewable energy currently accounts for 16% of energy consumption, wants to increase this level to 18% by 2020 and 60% by 2050. Germany also wants to reduce its energy demand across all sectors by 20% by 2020 compared to 2008, and by 80% by 2050. Finally, the country plans to reduce its GHG emissions by 40% by 2020 and between 80% and 95% by 2050. The Germans call this energy transition process the Energiewende.

While the events in Japan have reignited the debate on nuclear technology and safety in many European countries, Germany is firmly committed to phasing out nuclear power. All of its targets are set against a backdrop of a total and accelerated phase-out of nuclear power by 2022, in a country that has historically been cautious about the use of nuclear technology in its energy mix. This is evidenced by the relatively small and constant share of nuclear power in the German energy mix. For example, nuclear energy accounts for more than 70% of electricity production in France, compared with only around a quarter in Germany.

Issues and difficulties surrounding the development of renewable energies

Firstly, as things stand, the shortfall in nuclear production, linked to the shift in the energy mix towards phasing out this technology, cannot be compensated for by 2022. Germany will therefore have to significantly increase its energy imports, thereby burdening its trade balance. Secondly, the goal of reducing energy consumption will be very difficult to achieve, as it would require a radical change in people’s lifestyles, as well as in the way businesses operate. Finally, reducing GHG emissions by such a significant amount would also require the virtual abandonment of fossil fuels, which are high CO₂ emitters, and a significant expansion of renewable energies. However, this would mean investing heavily in these technologies.

In this context, achieving a balance between energy supply and demand seems highly unlikely, at least in the short and medium term. To achieve this balance, Germany will inevitably have to go through a period of increased energy production based on fossil fuels. Even if this increase involves the increased use of gas, which emits less CO₂ than coal and oil, it will still run counter to the goal of reducing GHG emissions. Furthermore, as Germany is not a gas producer, it will necessarily have to turn to its Russian trading partner, thereby reducing its energy independence.

Germany has set itself the target of achieving 35% renewable energy in its energy mix by 2020, and 80% by 2050. However, this laudable goal is confronted with unavoidable physical realities. Germany does not benefit from particularly favorable wind conditions, the country suffers from unfavorable sunlight conditions, and finally, its hydraulic capacity is already almost saturated. All these factors mean that Germany’s ability to rely on renewable energy to provide the energy it needs appears to be limited. Under these conditions, and if Germany persists with this policy, the solution necessarily lies in the development of new technologies and research and development (R&D). The aim is to increase the capacity of naturally limited renewable energy resources. One of the priority areas for development is the possibility of storing renewable energy, particularly wind energy. Unlike nuclear or fossil fuels, which can be stored and used as needed, renewable energy is by definition dependent on climatic conditions and is mostly non-storable. It must therefore be used as soon as it is produced. Furthermore, its transport poses a problem. Networks will therefore need to be developed to channel these energies and distribute them throughout the country, rather than just where they are produced. It should also be noted that these factors partly explain why Germany, unlike other European countries, does not wish to tax imports of low-cost Chinese solar panels.

Significant economic consequences and costs

The phase-out of nuclear power will cost several hundred billion euros by 2020. In 2011 alone, the additional cost of renewable energies was almost €14 billion, including around €7 billion for photovoltaics alone. According to initial estimates, the investment required to develop wind power will amount to around €400 billion by 2020. The cost of dismantling the nuclear fleet is estimated at between €200 billion and €400 billion by 2020. Ultimately, the Energiewende energy transition could cost more than €2 trillion, a colossal amount even for the world’s fourth largest economy.

Nuclear energy has the undeniable advantage of being the cheapest to produce and use. Abandoning it will therefore inevitably lead manufacturers to resort to more expensive energy sources: oil, gas, renewable energy, etc. Electricity costs will therefore increase and be passed on to production costs. In this context, manufacturers will lose competitiveness in a world where this aspect is a key factor in economic success. Even if the government puts in place support and subsidy systems for these activities to make them more profitable, the fact remains that these subsidies will have to be financed by taxes, either immediately or in the future. Furthermore, these hypothetical subsidy systems are likely to be poorly received by Germany’s trading partners, which could then take retaliatory measures for non-compliance with competition rules.

Conclusion

Ultimately, it will be households that bear the additional costs associated with the phase-out of nuclear energy and the development of renewable energies. They will have to pay these additional costs first through higher electricity prices, second through price increases caused by higher production costs, third through the financing of this energy transition, which will take place over several years, and fourth through tax increases if these renewable energies are subsidized. They may even have to bear another cost in terms of jobs if the decline in the competitiveness of German industry leads to a loss of export market share and therefore a decline in activity, resulting in an increase in layoffs.

Of course, employees are not yet in this situation, but it is nevertheless one of the possible mechanical effects. It seems that German households are beginning to anticipate these consequences. After having massively supported this initiative, without having measured the consequences it would entail, more and more of them are now questioning the relevance of such a choice in the medium and long term.