Women’s economic empowerment: a key tool for development

Summary:

– Gender equality and women’s economic empowerment are included in the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDG 3) and are considered a key lever for achieving the other seven goals.

– In 2012, the World Bank Report revisited the definition of development from a gender perspective to refocus the debate on the place of women in the global economy.

– Even today, women are the primary victims of poverty and their potential is underutilized compared to that of men.

– In 2012, 70% of people living on less than $1 a day were women and girls[1]. Women’s work accounts for 58% of all unpaid work.

– According to a study by Booz & Company (2012), increasing the employment rate of women to the same level as men would have a direct positive impact on the GDP of many countries.

In January 2014, BSI Economics addressed the issue of women’s work and their role as a source of development in an article by Axelle Fofana « Policies to promote women’s employment as a source of development . » We return to this issue with a more specific focus on women’s economic empowerment.

Today, gender equality is at the heart of the development issue. In the « capabilities » approach put forward by Amartya Sen, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics (1998), development is defined as « the equal freedom of a person to choose between possible ways of life. » In 2012, the World Bank’s report « Gender Equality and Development » took up the Nobel Prize winner’s definition from a gender perspective. Development is thus characterized as « a process through which the freedoms of men and women are expanded equally. » « Gender » refers to all the social, behavioral, and cultural attributes, as well as the norms and expectations associated with being a man or a woman.[2]Gender equality and women’s economic empowerment are included in the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDG 3) and are considered a key lever for achieving the other seven goals. Women’s economic empowerment is recognized as a fundamental right.

However, recent studies show that women are a powerful source of development. According to estimates by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (2011), if women-led farms were given equal access to resources (seeds and fertilizers), the number of people suffering from chronic hunger would decrease by 100 million worldwide. Similarly, a study by Booz & Company (2012) found that increasing the employment rate of women to that of men would have a direct positive impact on the GDP of many countries where gender discrimination is most prevalent. Egypt’s GDP would increase by 34%, the United Arab Emirates’ by 12%, South Africa’s by 10% and Japan’s by 9%.[3]

Reminder of the concepts of gender andwomen’s economic empowerment

The concept of gender refers to three main dimensions: the accumulation of endowments (education, health, and physical assets); the use of these resources to create income-generating economic opportunities; and the impact of these actions on the well-being of individuals and households. Any constraints affecting any of these aspects result in a reduction in well-being.

Economic empowerment is defined as a process consisting of two main components: resources and opportunities. Production resources are the endowments that women need to develop economically. These include financial resources (income, savings, credit), tangible assets (land, housing, technology) and intangible assets (skills, technical know-how and social recognition). However, having these resources does not necessarily mean that women enjoy economic autonomy. They must be able to decide how to allocate these assets and use them when undertaking profitable economic activities. Yet in most countries, women have limited access to and control over resources compared to men.

Women’s economic empowerment requires a holistic approach that integrates different facets: culture and traditions that shape the roles assigned to women and men; health, because women[4]suffer disproportionately from deficiencies in public health services. Women are overrepresented among the world’s poorest people. In the informal sector, they are particularly vulnerable to disease and are unlikely to be able to afford private health care. Women’s ability to allocate the resources necessary for their economic success and their inclusion in the decision-making process of their families, communities, and governments directly impacts the improvement of their living conditions.

Economic empowerment therefore refers to women’s » agency, » defined as their ability to make decisions and act on them. Even today, women are the primary victims of poverty and their potential is underutilized compared to that of men. According to UN Women figures, in 2012, 70% of people living on less than $1 a day were women and girls. They account for 58% of all unpaid work. In developing countries in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, they typically work 12 to 13 hours more than men per week. Women make up 43% of the global agricultural workforce, yet they own three times less land[7]. The proportion of women in paid employment in the non-agricultural sector is less than 20% in the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia, and less than 35% in sub-Saharan Africa[8]. Up to 45% of the poorest women have no say in decisions about how their own income is managed[9].

Women’s economic empowerment is considered an essential tool for promoting economic growth and development.

1. Current situation

1.1 Significant progress made for women over the past 25 years

The last 25 years have seen the most significant progress in terms of gender equality.

Firstly, disparities in primary education have been significantly reduced worldwide. However, the most striking change has been in secondary education. There has been a reversal in the gap in secondary school enrollment rates, particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean and in East Asia, where the number of girls now exceeds that of boys. According to the World Bank report (2012), in 45 developing countries, girls outnumber boys in secondary schools. This trend is also observed at the university level in 60 countries.

Life expectancy for women in low-income countries has increased significantly. Between 1960 and 2012, it rose by an average of 20 years compared to that of men.

Approximately half a million women have entered the labor market over the past 30 years. This increase is mainly linked to the rise in women’s participation in paid work in developing countries. In 2012, women accounted for 40% of the global workforce.

1.2 Other significant disparities persist

The excess mortality of men worldwide in 2008 was estimated at 1 million compared to 6 million for women.[10]In low- and middle-income countries, an estimated 3.9 million women die each year, of whom two-fifths die before birth,one-sixth during early childhood, and one-third during their reproductive years. These figures are rising in sub-Saharan Africa in countries where HIV/AIDS continues to rage.

In South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, despite the progress made, the enrollment rate for girls in primary and secondary education is significantly lower than that for boys.

Unequal access to economic opportunities: women are more likely than men to perform unpaid work within the family or to work in the informal sector. Women farmers generally have smaller plots of land and less profitable crops than men. Women entrepreneurs tend to be involved in less lucrative sectors and in smaller businesses.

In most countries, poor women have very limited bargaining power within their households, particularly in terms of access to and use of resources. In general, women are still underrepresented in political life and in the upper echelons of society.

2. Women’s economic empowerment as a driver of economic growth

2.1 The impact of gender equality on economic growth

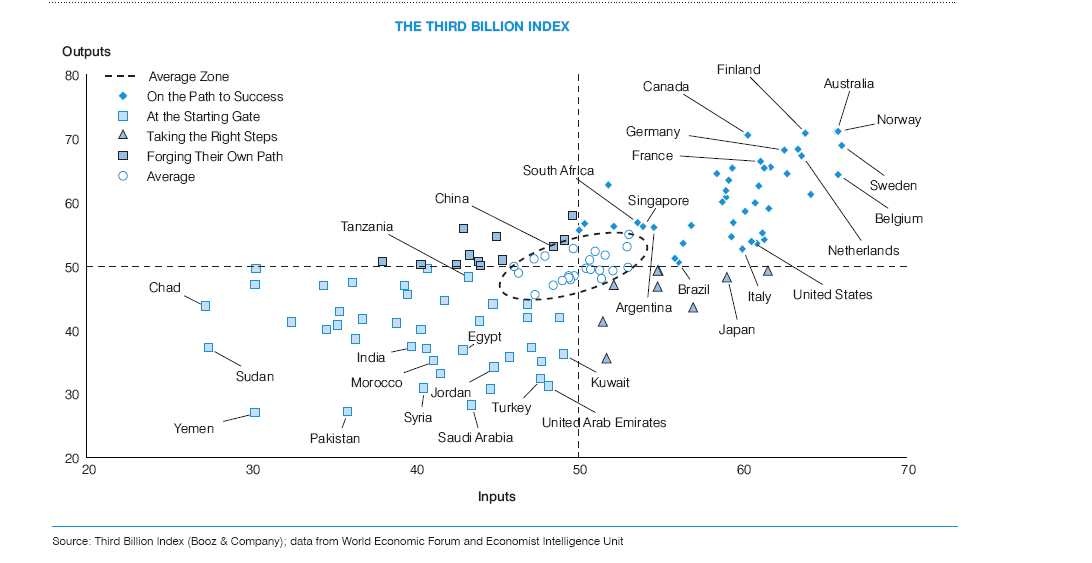

Numerous studies have highlighted the positive impact of promoting gender equality on economic development. Recent work by Booz & Company on a new indicator, the Third Billion Index, has demonstrated a significant correlation between women’s economic empowerment and economic growth.

The Third Billion Index is a composite indicator that shows the potential for women’s economic participation. Its objective is to rank countries according to the level of women’s economic empowerment effectively implemented within the market. It is composed of a set of indicators based on data collected by the World Economic Forum and The Economist Intelligence Unit from a sample of 128 countries.

To translate the economic status of women into quantitative terms, it uses indicators classified into two categories:

– « Inputs » present the measures (laws and policies) put in place by governments (in some cases, companies and NGOs) to promote the economic status of women in terms of education, employment, access to credit, etc. These inputs are grouped into three distinct aspects: the level of preparation (education and training in the broad sense) of women to enter the labor market, access to employment policies and support for business creation.

– Outputs include all visible dimensions of women’s participation in the national economy. In the long term, they reflect the economic, social, and political environment that is determined by inputs. The indicators taken into account include the gender pay gap, the number of women among technicians, senior business leaders, executives, etc.They are also grouped into three main aspects: integration into the labor market, equal pay for equal work, and progress made in the national economy (e.g., the ratio of women to men among managers, employees, and business leaders).

The Third Billion Index highlights a clear correlation between inputs and outputs. The indicator shows that countries whose governments are working to strengthen women’s economic empowerment have superior economic performance.[11]

These results are shown in the graph below. Countries are classified into five distinct groups: on track to succeed; at the starting line; taking appropriate measures; charting their own course; and average. We can see that the highest-ranked countries, in the « on track to succeed » category, have a high level of inputs associated with superior outputs and economic results. These are Western economies such as Australia, Canada, and Finland. In contrast, countries with low levels of inputs are characterized by lower economic performance. These countries are in the « at the starting line » category and include Laos, Nigeria, and Indonesia. The vast majority of countries in the sample are in this situation. The losses in terms of economic opportunities are therefore considerable.

According to their estimates, approximately 1 million women are likely to enter the labor market over the next decade. By increasing the level of female employment, GDP would increase by 5% in the United States, 9% in Japan, 12% in the United Arab Emirates, and 34% in Egypt.

The main findings of the Third Billion Index show that advances in women’s economic empowerment not only help to mobilize women’s participation in the labor market, but also have positive spillover effects in terms of economic growth and development (improvements in health, education, early childhood development, security, freedoms, etc.).

2.2 The impact of gender equality on development

Similarly, the World Bank Report (2012) highlights how gender equality contributes to development by acting through three main channels:

Increased productivity gains

Women now account for 40% of the global workforce, 43% of the agricultural workforce, and more than half of university students worldwide. The misallocation of women’s skills leads to considerable economic losses.

FAO studies have shown that equalizing women’s access to productive resources would increase agricultural production by 2.5 to 4%. For example, if women farmers had the same access to fertilizers as men, corn production would increase by 11 to 16% in Malawi and by 17% in Ghana[12]. Improving women’s property rights in Burkina Faso would increase household agricultural production by 6%, simply by reallocating fertilizers and labor equally[13]. Removing barriers to women’s entry into certain sectors or professions would lead to a 13-25% increase in per capita output[14.

Furthermore, recent work by Do, Levchenko, and Raddatz (2011) shows that in a context of trade globalization, gender disparities lead to even greater economic losses. They reduce a country’s competitiveness in the face of international competition. This is particularly true when the country specializes in exports of goods and services that can be produced by both women and men. The authors observed that industries that rely mainly on female labor develop more in countries where gender disparities are low.

Furthermore, encouraging the integration of women into the labor market also helps to address the rapid aging of the population, particularly in Europe and Central Asia.[15]In Europe, for example, the anticipated decline in the labor force of 24 million people by 2040 could be reduced to 3 million if the female labor force is strengthened.

Improving the living conditions of future generations

Women’s endowment, agency, and economic opportunities determine and shape the living conditions of future generations. The greater the resources allocated to women within the household, the greater the investment in children’s human capital, which translates into positive dynamic effects on economic growth.

Research conducted in many countries (Bangladesh, Brazil, Côte d’Ivoire, Mexico, South Africa, and the United Kingdom) shows that an increase in the share of the household budget controlled by women (through their own income or cash transfers) directly benefits children.[16]In Ghana, the share of assets and land owned by women is positively correlated with higher levels of food expenditure[17]. In Brazil, the growing share of women’s income (not from wages) is associated with a positive impact on the height of their daughters[18]. In China, a 10 percentage point increase in the average household income held by women leads to a one percentage point increase in the life expectancy of girls[19]. In Pakistan, children whose mothers have received an additional year of education spend an average of one hour more on homework and achieve better academic results[20. Improving women’s health and education therefore directly benefits future generations.

Improve women’s representation in economic, social, and political decision-making.

Promoting women’s individual and collective agency helps to improve the quality of institutions and decision-making at the political level. Women’s agency influences not only their ability to build human capital and seize economic opportunities, but also to transform society as a whole.

In the United States, women’s suffrage has brought the health issues of women and infants to the attention of political leaders, reducing infant mortality rates by 8 to 15%.[21]between 1869 and 1920[22. In India, the introduction of quotas for women in politics has been accompanied by an increase in the provision of public goods (health infrastructure, drinking water), a reduction in corruption, and an increase in the number of crimes against women reported and punished[23.

Furthermore, in many developed countries, the increase in women’s political representation, combined with their growing participation in the economy, has led to the introduction of policies and legislative measures promoting work-life balance in the organization of working time.

Over the past two decades, Latin America has been the region that has seen the most significant progress in women’s economic participation. Among 10 countries in this region, the World Bank estimates that two-thirds of this increase is linked to rising education levels and changes in family formation (later marriages and lower fertility rates).

Even today, according to estimates by the International Labor Organization (ILO), nearly half of the productive potential of the female workforce is not being utilized globally, compared to only 22% for men.

Conclusion

Gender equality and development are a two-way relationship.[24]The increasing reduction in gender disparities over the past 25 years has been the result of market forces, institutional change, and their interaction with economic growth through household decisions.

In general, progress has been greatest in countries where institutional and market forces, supported by economic growth, have aligned to encourage households and society to invest equally in men and women. Conversely, progress has been slower in countries where, despite high economic growth, institutional and market constraints have reinforced inequalities in terms of endowment, agency power, and access to economic opportunities.

Promoting women’s access to resources and strengthening their allocation decisions helps to generate a virtuous circle in which their agency determines the accumulation of wealth, which in turn affects individual and collective well-being in the medium to long term. This is why women’s empowerment involves transforming unequal power dynamics between men and women and providing access to tools and opportunities for economic success.

Notes:

[1] In 2012, 1.2 billion people were living on less than $1 a day.

[2] Definition taken from the World Bank Report 2012

[3] These estimates take into account losses in labor productivity caused by the arrival of new workers on the labor market.

[4] The term « women » refers to women over the age of 18 and those under the age of 18 in the rest of this article.

[5] Unpaid work refers to all productive activities carried out by individuals outside the formal labor market.

[6] World Bank, 2012.

[7] IFAD, 2012 and FAO, 2011.

[8] World Bank, 2013;

[9] IFAD, 2012.

[10] Male excess mortality is measured as the male/female ratio of the probability of dying at a given age; in this case, estimates are made for people under the age of 60. These statistics were estimated globally for the years 1990, 2000, and 2008. The methodology used is detailed in the World Bank report (2012) « Gender Equality and Development, » p. 120.

[11] Not taking into account all external factors (access to healthcare, political participation, legal status).

[12] Gilbert, Sakala, and Benson 2002; Vargas Hill and Vigneri 2009.

[13] Udry 1996.

[14] FAO, IFAD, and ILO, 2010.

[15] McKinsey & Company Inc. 2007.

[16] Haddad, Hoddinott, and Alderman 1997; Katz and Chamorro 2003; Dufl o 2003; Thomas 1990; Hoddinott and Haddad 1995; Lundberg, Pollak, and Wales 1997; Quisumbing and Maluccio 2000; Attanasio and Lechene 2002; Rubalcava, Teruel, and Thomas 2009; Doss 2006; Schady and Rosero 2008.

[17] Doss 2006.

[18] Thomas 1990.

[19] Qian 2008.

[20] Andrabi, Das, and Khwaja 2011; Dumas and Lambert 2011.

[21] Miller 2008.

[23] Beaman et al., forthcoming; Chattopadhyay and Duflo 2004; Iyer et al. 2010.

[24] The relationship between development and gender equality has been the subject of numerous studies examining the causal relationship between the two factors.

References

– Aguirre, D., L. Hoteit, et al. 2012. Empowering the Third Billion: Women and the World of Work in 2012. New York: Booz & Co.

See: http://www.strategyand.pwc.com/

– FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization), IFAD (International Fund for Agricultural Development), and ILO (International Labor Office). 2010. “Gender Dimensions of Agricultural and Rural Employment: Differentiated Pathways out of Poverty. Status, Trends and Gaps.” FAO, IFAD, and ILO, Rome.

– FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). 2011. The State of Food and Agriculture 2010–11. Women in Agriculture: Closing the Gender Gap for Development. Rome: FAO.

– IFAD (International Fund for Agricultural Development). 2012. Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment. Rome: IFAD.

– SACO/CESO, 2014. Women’s Economic Empowerment: SACO Perspectives. Canada: SACO.

– World Bank, 2011. World Development Indicators 2011. Washington, DC: World Bank.

– World Bank, 2012. World Development Indicators 2012. Washington, DC: World Bank.

– World Bank, 2012. World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development. Washington , DC: World Bank.

– World Bank, 2013a. World Development Report 2013: Jobs. Washington , DC: World Bank.

– World Bank, 2013b.Gender at Work: a companion to the World Development Report on Jobs. Washington, DC: World Bank.

– Andrabi, Tahir, Jishnu Das, and Asim Ijaz Khwaja. 2008. “A Dime a Day: The Possibilities and Limits of Private Schooling in Pakistan.” Comparative Education Review 52 (3): 329–55.

– Attanasio, Orazio, and Valérie Lechene. 2002. “Tests of Income Pooling in Household Decisions.” Review of Economic Dynamics 5 (4): 720–48.

– Beaman, Lori, Esther Duflo, Rohini Pande, and Petia Topalova. Forthcoming. “Political Reservation and Substantive Representation: Evidence from Indian Village Councils.” In India Policy Forum, 2010, ed . Suman Bery, Barry Bosworth, and Arvind Panagariya. Brookings Institution Press and The National Council of Applied Economics Research, Washington, DC, and New Delhi.

– Chattopadhyay, Raghabendra, and Esther Duflo. 2004. “Women as Policy Makers: Evidence from a Randomized Policy Experiment in India.” Econometrica 72 (5): 1409–43.

– Doss, Cheryl R. 2006. “The Effects of Intrahousehold Property Ownership on Expenditure Patterns in Ghana.” Journal of African Economies 15 (1): 149–80.

– Duflo, Esther. 2003. “Grandmothers and Granddaughters: Old-Age Pensions and Intrahousehold Allocation in South Africa.” World Bank Economic Review 17 (1): 1–25.

– Dumas, Christelle, and Sylvie Lambert. 2011. “Educational Achievement and Socio-Economic Background: Causality and Mechanisms in Senegal.” Journal of African Economies 20 (1): 1–26.

– Haddad, Lawrence, John Hoddinott, and Harold Alderman. 1997. Intrahousehold Resource Allocation in Developing Countries: Models, Methods, and Policy. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University.

– Hoddinott, John, and Lawrence Haddad. 1995. “Does Female Income Share Influence Household Expenditures? Evidence from Côte D’Ivoire.” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 57 (1): 77–96.

– Iyer, Lakshmi, Anandi Mani, Prachi Mishra, and Petia Topalova. 2010. “Political Representation and Crime: Evidence from India’s Panchayati Raj.” International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC. Processed.

– Katz, Elizabeth G., and Juan Sebastian Chamorro. 2003. “Gender, Land Rights, and the Household Economy in – Rural Nicaragua and Honduras.” Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Latin American and Caribbean Economics Association, Puebla , Mexico, October 9.

– Lundberg, Shelly J., Robert A. Pollak, and Terence J. Wales. 1997. “Do Husbands and Wives Pool Their Resources? Evidence from the United Kingdom Child Benefit.” Journal of Human Resources 32 (3): 463–80.

– McKinsey & Company Inc. 2007. “Women Matter. Gender Diversity, A Corporate Performance Driver.” McKinsey & Company Inc., London.

– Miller, Grant. 2008. “Women’s Suffrage, Political Responsiveness, and Child Survival in American History.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 123 (3): 1287–327. See article link: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3046394/

– Qian, Nancy. 2008. “Missing Women and The Price of Tea in China: The Effect of Sex-Specific Earnings on Sex Imbalance.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 123 (3): 1251–85.

– Quisumbing, Agnes R., and John A. Maluccio. 2000. “Intrahousehold Allocation and Gender Relations: New Empirical Evidence from Four Developing Countries.” Discussion Paper 84, Food Consumption and Nutrition Division, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC.

– Rubalcava, Luis, Graciela Teruel, and Duncan Thomas. 2009. “Investments, Time Preferences, and Public Transfers Paid to Women.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 57 (3): 507–38.

– Schady, Norbert, and José Rosero. 2008. “Are Cash Transfers Made to Women Spent Like Other Sources of Income?” Economics Letters 101 (3): 246–48.

– Thomas, Duncan. 1990. “Intra-Household Resource Allocation: An Inferential Approach.” Journal of Human Resources 25 (4): 635–64.

– Udry, Christopher. 1996. “Gender, Agricultural Production, and the Theory of the Household.” Journal of Political Economy 104 (5): 1010–46.